Career

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

There was a time in Kate Fullagar’s life, just after she graduated from Australian National University with an honours degree in history, that her exit from Canberra couldn’t come soon enough.

Born and raised there in the 1970s and ‘80s, long before the city gained its reputation as a progressive paradise, the younger Kate was part of a wave of young people fleeing what was widely seen as a cultural desert.

“For a long time,” she says, “it was fashionable in Canberra to think that the number one ambition you have in life is to leave it. Which I suppose I did share, because I did leave it.”

Armed with a one-way ticket and a strong suspicion that “life is elsewhere”, she fled the Antipodes bound for Britain, where she “fluked” a brief publishing job in Oxford. From there she made her way to the United States, where in 1998 she started a PhD at the University of California, Berkeley, in one of the world’s leading history programs. She describes studying there as “formative”.

“It gave me a lot of resources and allowed me to meet amazing professors and things like that,” she says.

And yet, one can sense that there’s a “but”.

“I don’t want to downplay all the wonderful things those experiences gave me, but I think the ultimate lesson was that the ideas aren’t grander in the Northern Hemisphere, that the people aren’t smarter and things aren’t always shinier and better. People struggle with the same historical questions and encounter the same issues about creativity.”

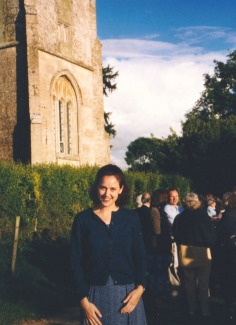

Kate on campus at Berkeley in 1998 (left); and at Oxford.

Having now shed some cultural cringe, she remains grateful for the time she spent overseas.

“It gave me the confidence to know that I didn’t have to keep wondering what was going on in other parts of the world,” says Professor Fullagar, who returned to Australia in 2002, settling in Sydney to work at Macquarie University before joining ACU’s Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences in 2020.

“I know that the debates they might have are very similar to the debates we might have here in Australia, and that we have as much to contribute to scholarship and history as they do.”

Through most of high school, Kate Fullagar was known as a champion swimmer, winning state and national medals and even representing Australia overseas.

Her success in the pool was thanks in part to her English mother, who was “very nervous about swimming and water”, and fretted about how to keep her children safe.

“My mother had this idea that every Australian child swims all the time,” she says. “She insisted on lessons from a very young age and kept us going for longer than most other children, and the result was that I became a very good swimmer.”

Kate showed potential and at 16 was offered a scholarship with the Australian Institute of Sport. She ultimately turned it down, realising that to accept would sacrifice her academic future.

“That seemed like a big decision to make as a young person, and it allowed me to realise that my academic education was important to me. Before that, I only ever thought of myself as a sporty person, but the truth was that I was probably never going to reach the very top in swimming at the Olympic level, and once I came to that realisation, the sacrifice simply seemed too big.”

Instead, she stepped out of the pool and turned her attention to her studies, developing an interest in history and eventually pursuing the subject at university.

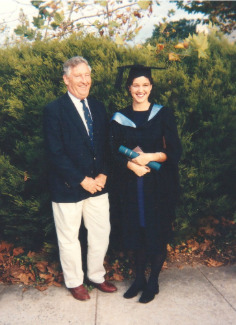

Kate on the ACT swim team in 1984 (left); and graduating from ANU.

In some ways, however, Kate was an unlikely historian.

She comes from a family of scientists, her parents moving from the UK to Australia in 1964 when her father was offered a research position at the CSIRO.

Having an interest in the humanities was “odd” in her family, and while her parents were happy to support any form of higher education, they were “a bit amused by history”.

“I think that everyone has a form of creativity and a wish to express themselves, and it could come out as research into genetics, or it could come of out creating things out of wood,” she says.

“I’ve always been interested in using writing as an expression for speaking human truths, and the discipline for me is to write about the past and argue with people in the present about the past.”

Through a career spanning more than two decades, Professor Fullagar’s writing and research has shed new light on many aspects of social and cultural history. She is recognised as one of Australia’s most distinguished historians, an award-winning scholar whose most recent book, Bennelong and Phillip: A History Unravelled, has earned her wide acclaim from her peers, and was shortlisted for the Prime Minister’s Literary Award.

Describing herself as “an historian of modern empire and Indigenous resistance”, she was originally drawn to the topic of imperialism due to her own background and upbringing.

“It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that my initial interest in British imperialism was because I was the direct child of one of the effects of the British Empire,” she says. “You can call my parents migrants, but their incredibly privileged way of accessing the Australian migration system was due to the fact that this was a former British settler colony. When you’re raised in that context, you know that the British Empire has been a global empire with global ramifications.”

This initial interest soon grew into something bigger.

“The more I wrote about the mechanisms and infrastructure of empire, the more I realised that I didn't want to just write imperial histories where Indigenous people were the objects on which empire enforces itself,” says Professor Fullagar, whose research has explored Britain’s encounters with various Indigenous societies, including the Polynesians of the eastern Pacific, the Cherokee of the American southeast, and the Darug-speakers of today’s Sydney.

“I started to think more about the Indigenous side of every imperial story I was telling, and because I have knowledge about how empires work, I can actually bring the two fields together to offer a reasonably nuanced and deep history of Britain, while also thinking about Indigenous agency in a sensitive and useful way.”

In both Bennelong and Phillip and her other recent book, The Warrior, the Voyager, and the Artist, Professor Fullagar uses biography to weave an authentic narrative of empire and its interactions with Indigenous societies.

Rather that writing singular biographies, she opted in both cases to place multiple historical figures together, telling their parallel stories in a manner that adds new depth and meaning to colonial history. As one reviewer put it, in relation to Bennelong and Phillip, “…no one can avoid having their ideas about invasion challenged to some extent by this remarkable book”.

Challenging narratives and casting new light on old stories is at the “the core of what academic historians do”, says Professor Fullagar, who is vice-president of the Australian Historical Association.

“We only write because we think there’s an important conversation that needs to go in a new direction, and that’s never an easy thing to achieve,” she says.

Take, for example, her conclusion that in the time of Bennelong and Phillip, conciliation was briefly attempted but was ultimately unsuccessful. Her original intention was for the book to be released shortly after the Voice Referendum, serving as her contribution to the task of truth-telling set out in the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

In the end, it was released 10 days before the referendum poll.

“In those 10 days, I tried desperately to spread the message that this is the kind of history you should keep in mind when you go to the polls,” she recalls. “This is a history of a conciliation that didn’t happen, that therefore didn’t lead to treaty between the settlers and the Indigenous, that has led to this permanent irresolution in Australian history that we have a chance to start changing if we vote ‘yes’ to the Voice.”

Kate in 2023 (left); and at the Prime Minister's Literary Awards.

The ultimate failure of the referendum was “sobering” to her and many other academic historians, she says, demonstrating that despite years of historical revisionism and truth-telling, Australian history is for many people still up for grabs – both in the wider community, and in the buildings perched on Canberra’s Capital Hill.

As for her hometown, in recent years Professor Fullagar has been reassessing her own history – specifically, her connection to the place she once sought to escape.

In 2020, after 14 years in Sydney, she came full circle, joining the hordes of Canberrans who have returned to the city and been charmed by its newfound cachet.

“It’s certainly become more of an interesting town, and it’s been gratifying to justify my decision and my lingering fondness for the place,” she says.

“As an historian who knows a bit about the history of the creation of Canberra, it does feel like it took 100 years to realise Burley Griffin's vision, but I think it’s happening, you know, finally.”

Kate Fullagar is a Professor of History at ACU’s Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences, a fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities, and Vice-President of the Australian Historical Association. She specialises in the history of the 18th-century world, particularly the British Empire and the many Indigenous societies it encountered.

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008