Community

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

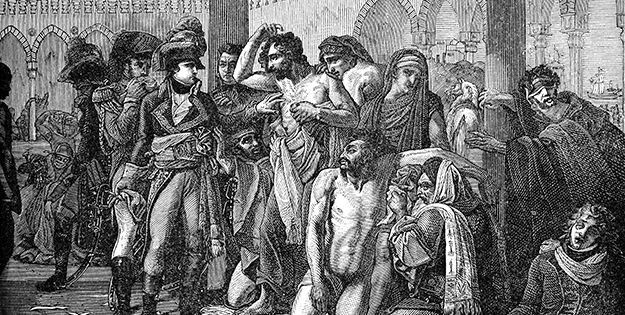

In The New Yorker magazine in 2005, the writer Joan Acocella described the Black Death – the epidemic of bubonic plague that tore through Eurasia in the mid-14th century – as being “like a disaster movie: a menace stalks the land; cries go up in the streets; millions of people die, not including you and me".

The plague may have been the world’s deadliest pandemic, but it’s history: it happened to other people, in another time.

Then in early 2020, with very little warning, the novel coronavirus began its devastating journey across the world, infecting millions and wrecking havoc on the global economy.

We suddenly became extras in our own real-life disaster film, and the experiences of our forebears — people who’ve lived and died through the plague and other society-shifting outbreaks — became easier to relate to. And despite the centuries that separate us, our responses have been remarkably similar.

Taking their cues from the Black Death, medieval historians quickly identified patterns of behaviour that emerge during times of crisis; patterns that are invisible to those who close their eyes to the past.

“When you look back over the centuries, human behaviour tends to follow patterns, and so history gives us a predictive power or a model for how people respond to these kinds of events,”

says Dr Matthew Champion, a senior research fellow in medieval and early modern studies at the Institute for Religion and Critical Inquiry.

“Medieval historians have been predicting what will happen, and so far we have been right on the money. We predicted the economic impacts, the hoarding behaviour, the racist rhetoric …”

Historians know, for example, that societies experiencing outbreaks tend to look for scapegoats and spread misinformation. "When the Black Death started to spread through Europe, there were accusations against Jews of well poisoning, and that led to widespread violence again Jewish communities,” says Dr Champion, author of the award-winning book, The Fullness of Time.

“We’ve seen similar things happen to

Chinese communities in this current period, with many leaders blaming Chinese communities

for coronavirus and developing conspiracy theories about its spread.

“There have been 5G conspiracies, Wuhan labs conspiracies and violent reprisals against international students. Thankfully, it’s been on a much smaller scale. But these are similar kinds of impulses motivating people, which demonstrates some consistency in how people behave under pressure.”

It was eventually accepted that the Black Death originated in Central Asia and entered Europe in 1347, when 12 merchant ships docked at the port of Messina in Sicily.

The role of these so-called “death ships” in spreading the plague and other pandemics has prompted comparisons with COVID-19, where cruise ships have also been responsible for major outbreaks.

As coronavirus case numbers rose in

Australia, passenger ships anchored off the coastline were banned

from entry and told to leave our

territorial waters. Similarly, many merchant ships were turned away from

European ports during the Black Death, with those permitted to enter ordered to

quarantine for 40 days.

The practice of quarantine emerged during the Black Death, Dr Champion says, and it became even more prevalent in subsequent pandemics. (The word itself is derived from the Italian quarantena, meaning “space of 40 days”.)

Like those living through COVID-19, people guarded against infection from the plague through self-isolation, a custom first employed in medieval times. But the practice of social distancing – almost universal through the coronavirus pandemic – is a relatively new phenomenon.

Its adoption as the dominant measure

in pandemic response came in 2007, when the medical historian Howard Markel

studied the different

approaches of US cities during the 1918 influenza outbreak.

“Markel found those towns that had quickly shut down public events had far lower mortality rates than those that had stayed open,” Dr Champion says.

“And so the structured notion of

depriving a virus of its host through state-sanctioned social distancing came

out of a historical analysis of the 1918 pandemic.

“It’s not a medieval story, but it’s an interesting one, and it shows you the importance of having historians out there analysing and responding to these kinds of events.” While it’s useful to employ historical knowledge to identify similarities between past pandemics and current ones, it also pays to be mindful of the differences.

The most obvious divergence between the Black Death and COVID-19 thus far is that the former was much deadlier, wiping out between 40 and 60 per cent of the population of Eurasia.

“With such a huge mortality rate, you’re really looking at quite substantial economic and social changes, and that will continue to have profound effects for many years afterwards,” says Dr Champion, whose research has explored the history of medieval senses and emotions.

These points of comparison allow us to put our situation into perspective.

“If you were living in the 14th century in Italy, or in London during the Great Plague of 1665, you’d be locked up in your house, in some cases with watchers making sure you don’t leave, and with no effective medical treatment and no mass systems of communication,” he says.

“That’s a far, far worse situation

than the one we have faced. And so that allows us to say, ‘Well, given that

radically different situation, how can we use our technological systems to look

after each other and support each other, and to do something positive?’

“It gives you the capacity to

actually feel different about the pandemic; not to feel good about it, but to see where there are the potentials for good in

the midst of a bad time.”

“It gives you the capacity to actually feel different about the pandemic; not to feel good about it, but to see where there are the potentials for good in the midst of a bad time.”

The creativity that arises from pandemics is an example of the potential for good.

Out of the Black Death came Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron, a collection of stories regarded as a literary masterpiece, which shed light on life during the plague.

Coronavirus has also borne creative fruit, with writers, musicians and visual artists exploring new ways in which to share their endeavours, and families getting creative with how they approach schooling and caring for their children.

It may yet produce a Boccaccio-esque masterpiece, giving future generations a window into our lives.

“There are countless historical examples of people being culturally productive during pandemics,” Dr Champion says, “and this creativity is definitely a positive parallel, in that it can give people hope and connection.”

Perhaps the most important pattern that emerges during pandemics — past and current — is that they spur calls for social reform.

“Crisis provides an opportunity for public conversation, and this appetite and energy for social and moral reform can be incredibly powerful. These are times that society can come together, and hopefully emerge improved.”

Dr Matthew Champion is a senior research fellow in medieval and early modern studies at the Institute for Religion and Critical Inquiry. His research has focused on how time was perceived and experienced from the 14th to 16th century. He is currently writing his third book, supported by a major Australian Research Council grant, The Sounds of Time.

Interested to learn more? Explore our courses at ACU.

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008