Global

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

On the morning of 20 June 1982, at a town named Vung Tau in southern Vietnam, 101 men, women and children set off on an overloaded fishing boat bound for the Philippines, joining countless others who fled their homeland after the communist takeover of 1975.

Anh Nguyen Austen was on that boat. She was six years old at the time. One of her key memories of the voyage was a white lie her mother told her to keep her from falling overboard: “[She] told me that there were ghosts of the dead, those that drowned in the ocean, and if I went to the edge, they would pull me in.”

Two days into the journey, the wooden fishing boat was caught in a severe storm. The engine quit working and the walnut-shaped vessel was at the whim of the weather and the waves.

Those navigating the boat quickly realised they did not know which direction they were heading. They were lucky enough to have escaped the worst of the storm and drifted into the hands of their rescuers.

Every single person on the 101 Boat, including an 81-year-old man, was saved by the French humanitarian group Médecins du Monde, who roamed the South China Sea on their vessel Le Goëlo searching for refugee boats in need of help.

The dramatic rescue was filmed for a video promoting Médecins du Monde’s activities. Anh Nguyen Austen and many others on the 101 Boat only became aware of the footage many years later.

Anh’s memory of the rescue gives an insight into the experience of other Vietnamese refugees: “What I can remember is the fishing net dropped along the side of the huge boat. I thought surely we would fall into the ocean and die at this moment of rescue. We were so exhausted, there was no energy left in me to climb. I could see the waves lashing their claws upon the boat and people above extending their arms towards us.”

Some three decades later, Anh Nguyen Austen, early-career historian, arrived in Paris on a research trip.

She was midway through her PhD at the University of Melbourne, where she explored refugee history through interviews with Vietnamese migrants who’d entered Australia in the 1970s, and investigated the role of Facebook in developing global migrant communities, connecting former refugees who’d been in the same boat or camp.

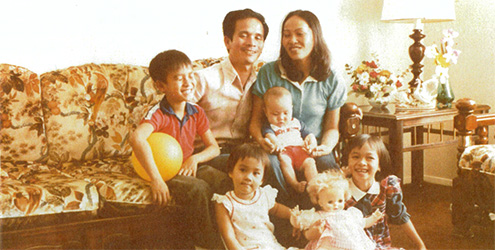

A young Anh (right) with her family.

Armed with a photo of a real-time reunion of her fellow 101 Boat survivors in France, she went on a search for a doctor who was on the vessel Le Goëlo when it came to the aid of the boat.

The doctor in question was Vietnamese, but he had left his country before the fall of Saigon to be trained in Paris. When the exodus from Vietnam hit crisis point in the early 1980s, the doctor joined Médecins du Monde on its mission to rescue refugees in the South China Sea.

With the help of her colleague, the Vietnamese and French scholar Tess Do, Anh was able to track down the doctor in Paris.

“When I found Dr Hien, who was part of my rescue, I was frozen,” she says. “At that moment, I had no capacity as a PhD student. I didn’t even ask any questions. I was at a loss for words and in a state of numb shock. My mind was completely empty.”

This moment is an example of what Anh terms “survival awe”. It’s an emotion she has witnessed in others at the real-time reunions of Vietnamese migrants who fled communist rule.

“At these reunions, these moments of ‘survival awe’ happen often,” says Anh, who completed her PhD in early 2020, the year she joined ACU. “Hundreds of thousands of people died at sea on these boat journeys, and yet here we are at a gathering in another country, sharing a meal, listening to Vietnamese music, reminiscing and taking pictures of each other.”

Finding Dr Hien in Paris set off a chain of events that would reshape Anh Nguyen Austen’s academic career, and also, her life.

Three years later, in 2019, she returned to France to attend a Catholic mass and public ceremony for the survivors of the 101 Boat. While there, she conducted oral histories with her parents and village friends who had organised the escape from Vietnam.

These interviews would form the basis for a ground-breaking piece of multidisciplinary research that explores the historical and environmental conditions surrounding the 101 Boat’s rescue.

As discussed in the study, most of the passengers on board the boat were devout Catholics. When the storm hit, putting the vessel in danger of succumbing to the sea’s force, the passengers placed their hope in the belief of God’s command over the journey.

In the oral history interviews carried out by Dr Austen, the adults explained their safe passage as an act of divine intervention.

Dr Hien speaking at reunion of 101 Boat survivors.

“Rain and sunshine are also the will of heaven, and heaven created the storms,” said Bac Hoa Gai, while Ann Tran expressed the view that, “God created the storms so as to put 101 of us into the cradle of the Le Goëlo ship.”

Realising the opportunity to expand on the oral histories and historical analysis of the 101 Boat journey, Dr Austen and her ACU colleagues, Professor Joy Damousi and Dr Mary Tomsic, sought the input of ocean engineers, to shed light on the environmental conditions the boat was forced to contend with.

Together with their collaborators Dr Filippo Nelli and Dr Alessandro Toffoli, the historians determined that the survival of the 101 Boat could be understood in religious terms as an act of God, or in scientific terms, by using mathematical models to examine factors such as wave height, length and frequency, and wind speed and direction.

The research team found that the conditions the boat encountered were indeed extreme, with wave heights at the eye of the storm at levels expected once in a hundred years. Yet the boat somehow remained at the edge of the storm, where the waves were much smaller.

The ocean “both imperilled and yet saved the boat and its inhabitants”, the researchers say, “(almost) pushing it to a position where it could be rescued”.

This scientific narrative does not supersede the historical accounts of survivors, or seek to tell the ‘truth’ about the journey. Rather, it sheds new light on how the rescue was possible, adding depth to the memories of survivors, and demonstrating how those on board were dependent on ‘acts of nature’ for their survival.

For her part, Dr Austen describes the emergence of this new information on the 101 Boat journey as “a jovial moment”.

“We knew we survived something big, but we didn’t realise the magnitude,” she says. “And now we have this data which shows us that historically speaking, storms of this magnitude were incredibly rare. It proves just how lucky we were.”

Meanwhile, she believes that the “oceanic humanitarianism” referred to in the study, which accounts for both the human intervention and the ocean’s ‘actions’ in the rescue, signalled the beginnings of a broader legacy of humanitarianism.

“Humanitarianism as a concept is very powerful,” she says, “and if you think about it, those refugees who were saved — whether they were saved by God, or by the ocean, or by the rescuers — they went on to engage in future humanitarian efforts, thereby contributing to this history of former refugees engaged in humanitarianism.”

In recent years, Anh Nguyen Austen has herself been a keen contributor to refugee research and engagement.

Since migrating to Australia from the United States, she has been heavily involved in a diverse range of community-based activities, both as part of her research, and on a voluntary basis.

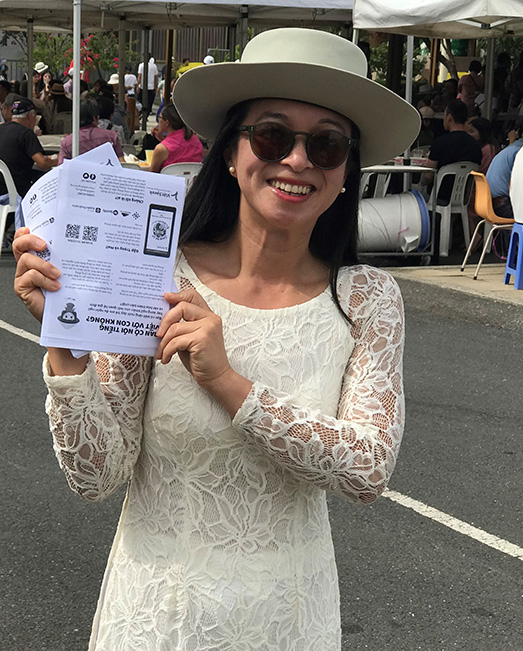

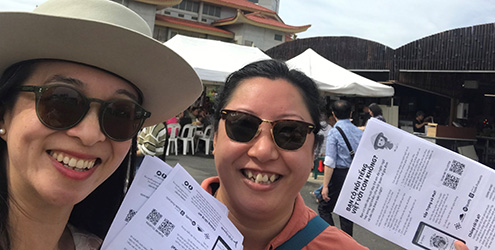

Dr Austen with VietSpeak community organiser, Hong Tran.

Dr Austen is a founding committee member of ViêtSpeak, a community-based language advocacy group that produces the podcast Growing Up Bilingual in Australia. She donates her talent as a cook and storyteller with Free to Feed, a social enterprise that supports refugees and new migrants in Australia, and volunteers with Museum Victoria, schools, and not-for-profits to co-create interdisciplinary projects for local and public history engagement.

Her academic work is heavily tied to her humanitarianism and community engagement. Dr Austen’s research has included teaching workshops using game design and live storytelling, and developing video game prototypes with a software engineering student to show how ordinary people become refugees.

“I approach my research as an exchange or a dialogue,” she says. “It brings in my own experiences as a displaced person, and allows others who’ve had similar experiences to share their insights, so they don’t feel alone in it. I think and hope it’s been mutually beneficial, creating a sense of belonging — for myself and others.”

Her recent work with Vietnamese-Australians has found that child refugees are at the cultural frontier: they witness their parents’ struggle for food and shelter, but growing up in Australia generates higher aspirations for creative fulfilment.

“They are trying to acquire the belonging that their parents never had,” says Dr Austen, whose future research will explore the phenomenon of refugee entrepreneurship, and the unique drive of displaced people to contribute to the common good.

“Many of these refugees were once the recipients of humanitarian aid, and you see so many instances of them now leading and designing, creating new histories of humanitarianism and moving beyond this view of refugees as just victims or beneficiaries.

“If you look at it metaphorically, you can see it as throwing a stone in the water — it creates these ripples and sets in motion a whole new movement, a new wave of hope, and a new type of humanitarianism.”

Dr Anh Nguyen Austen is a cultural historian with ACU’s Research Centre for Refugees, Migration and Humanitarian Studies at the Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences. Her forthcoming book, Vietnamese Migrants in Australia and the Global Digital Diaspora: Histories of Childhood, Forced Migration, and Belonging, will be published by Routledge in late 2022.

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008