Global

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

In a village in the mountains of Nepal, an elderly grandmother sits outside her home, her eyes cloudy with untreated cataracts. “All of my children, I used to know their faces,” says Manisara Gaha in a documentary called Open Your Eyes. “But I’ve never seen my granddaughter. Maybe her toes are just like mine.”

Cataract is a common eye disease that accounts for around six in 10 cases of treatable blindness in Nepal, affecting thousands like Manisara each year.

In Australia and much of the developed world, a simple surgery can restore sight. An ophthalmologist replaces the patient’s cloudy lens with an artificial one that allows them to see clearly within hours.

In developing countries like Nepal, cataracts are commonly left untreated. Many patients live in remote areas where ophthalmologists and medical facilities are scarce; others are either unaware of the treatment or unable to afford it.

“Ophthalmology can have a life-changing impact,” says Tia Day, one of 10 ACU nursing students who recently visited Nepal and observed both the potential to cure blindness, and the barriers to treatment.

“I learned the impact and prevalence of eye disease, especially cataracts, and how simple and effective cataract surgeries are. Community outreach and clinics are vital in increasing access to care in countries like Nepal, and healthcare systems in developing countries often rely on international support.”

It was this understanding of Nepal’s eye health challenges that led ACU to partner with Open Eyes Nepal, a not-for-profit organisation that’s raising awareness of a rare condition called retinoblastoma.

Like cataracts, retinoblastoma can cause blindness – but the parallels end there. Cataracts affect older adults and are usually treatable through surgery. Retinoblastoma is an aggressive childhood cancer that often requires removing an eye to save the child’s life.

What’s more, treatment is complex and costly, putting it out of reach for many families.

“It can be a long and drawn-out process,” says Dr Purnima Rajkarnikar Sthapit, an ocular oncologist and oculoplastic surgeon who co-founded Open Eyes Nepal in 2021.

“With cataracts, you have a one-time surgery and you’re done. Retinoblastoma treatment can take two or three years from diagnosis through to surgery and rehabilitation, and even families from well-off backgrounds can struggle to find the money.”

Dr Purnima Rajkarnikar treated her first retinoblastoma patients more than a decade ago in India, which records more cases than any other country.

Just as in Nepal, low awareness of the condition is a major challenge, as are the hefty treatment costs. Yet some of her Indian patients were fortunate.

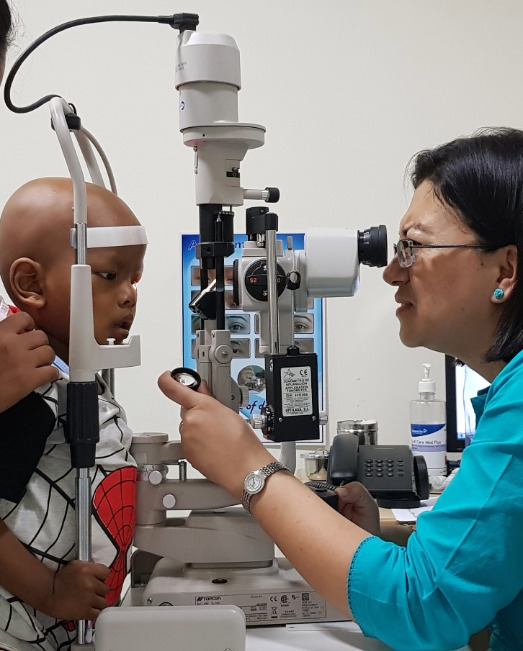

Dr Purnima with a patient; and (right) ACU students in Nepal.

“There was an organisation there that helped these young families,” says Dr Purnima, who did her clinical fellowship at the Centre for Sight in Hyderabad, with a pioneer of retinoblastoma treatment, Dr Santosh Honavar.

“This organisation provided not only the money for treatment but also the psychological support, which is very important, because to have cancer in the eye of your child is stressful and challenging.”

When she returned home to Nepal and established herself as a surgeon at the Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology, Dr Purnima met many more retinoblastoma patients – and many more parents who couldn’t afford the cost of care.

Timely treatment of retinoblastoma is crucial. Without it, death is almost certain.

“We’d see families whose children were recently diagnosed, and they wouldn’t tell us that they didn’t have the money for treatment – they’d just go home,” she says.

“If they don’t come back for the follow-up appointment, maybe the child dies. So later I’d call them, and they’d say, ‘We don’t have the money’.

“As a surgeon, that was heartbreaking to hear, because I have the degree and the skills to treat them, we have the hospital and we have the facilities, but still we were not able to help. It made me feel so powerless.”

In 2017, Dr Purnima gave a presentation at the World Cancer Congress in Kathmandu. Her lecture, delivered to some of the globe’s leading cancer researchers and healthcare professionals, explained how children with retinoblastoma often needed to have their cancerous eye removed and replaced with a glass eye.

It was there that she connected with Professor Suzanne Chambers, now the executive dean of ACU’s Faculty of Health Sciences.

“After listening to that lecture, Dr Suzanne came to me and said, ‘I want to help you’,” Dr Purnima recalls.

Professor Chambers launched Open Eyes Global in 2018. The charity has since helped scores of Nepalese retinoblastoma patients whose families could not afford a customised prosthesis.

One the many Nepalese retinoblastoma patients who have received a customised prosthetic eye.

Three years later, Dr Purnima founded Open Eyes Nepal with an expanded remit. Beyond providing prosthetic eyes to patients free of cost, it also spreads awareness to enable early detection, funds surgical and laser treatment and ongoing rehabilitation, and provides guidance and support to parents.

Since 2023, when ACU announced its partnership with Open Eyes Nepal, 88 patients have had free retinoblastoma treatment, and 57 now have a custom-made prosthetic eye – care that would otherwise be largely inaccessible.

Dr Purnima performed the surgery on every one of them.

There’s Sejan, a boy from the Gorkha district who received treatment after his first birthday, and has been cancer-free ever since. Or Januka, a three-year-old girl whose mother, a single parent who worked at a carpet-weaving factory, couldn’t afford to pay for care.

Other families have travelled from all over Nepal for free treatment, from places like Mahottari, Bardiya and Dailekh.

“It makes me immensely happy to help these patients and help these families,” says Dr Purnima, who has worked at the Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology since 2016, and has performed surgery on hundreds of retinoblastoma patients.

“We’re very lucky to have this partnership with ACU. We can change lives. We do change lives.”

In early 2025, when Tia Day and her fellow ACU nursing students were in Nepal for their short-term international study experience, they encountered patients like these – people whose lives could be transformed through medical treatment.

At the Tilganga Eye Hospital and the Grande International Hospital, they had the rare opportunity to observe live surgery.

“None of the students had ever been in an operating theatre before,” says Darren Jacob, a nursing lecturer at ACU’s Melbourne Campus, who led the study tour alongside Associate Professor Rebecca O’Reilly. “That was a highlight for many.”

Tia Day (top, centre) with other ACU nursing students at the Tilganga Institute of Ophthamology.

Meeting patients at the Kanti Children’s Hospital was both enlightening and challenging, says Tia, who one day hopes to work in paediatrics. She struggled with the emotional toll of seeing preventable blindness, particularly in children.

“We witnessed some confronting ethical dilemmas,” she says.

Despite these challenges, the trip deepened Tia’s passion for nursing. She and her peers saw firsthand how targeted outreach and partnerships can change lives for the better.

“We are delighted to hear the stories of children whose lives have been transformed by our work with Open Eyes Nepal and the Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology,” says Chris Riley, ACU’s Pro-Vice Chancellor (Global and Education Pathways).

“What started out as a community engagement initiative has expanded to become an invaluable clinical development opportunity for ACU students, staff and healthcare professionals across Nepal.”

While eye health is still a major issue in Nepal, the country has made significant progress in recent years, consistently demonstrating a remarkable reduction in the prevalence of blindness.

“We are a success story,” says Dr Purnima, whose research has explored the effects of various eye conditions on the Nepalese population. “Eye disease is a global problem, but the treatment available in Nepal is world-class treatment.”

Dr Purnima is one of Nepal's leading ophthamologists.

Much of the progress stems from the work of the Tilganga Institute, which in the early 1990s worked closely with the Fred Hollows Foundation to launch the Nepal Eye Program – a cornerstone in the fight against blindness in Nepal.

There is still much work to be done, Dr Purnima adds, particularly in raising awareness of the many eye conditions that can cause blindness if not treated early.

“Raising awareness is crucial,” she says. “It’s the most important thing.”

This goes not only for the young children and families affected by life-threatening retinoblastoma, but also for the hundreds of thousands of older adults who fall victim to debilitating cataracts each year in Nepal. Although the case estimates vary, it is without a doubt the most prevalent eye condition in the country.

Which brings us back to Manisara, the elderly Nepalese woman whose cloudy eyes prevented her from seeing her cherished granddaughter.

In the end, the surgery restores her sight, as it does for many Nepalis who receive treatment for cataracts.

Now able to see, she confirms that her granddaughter’s toes really are just like hers.

“So, that’s what you look like,” Manisara says, chasing after the child. “I see you, and here I come!”

Keen to change lives through a career in healthcare? Explore the options.

Find out more about ACU’s international partnerships.

Donate to Open Eyes Nepal and Open Eyes Global.

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008