Lifestyle

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

There's a battle going on in sports science. Exactly how much fat, carbs and protein athletes should consume for optimal performance has been fiercely debated for decades, but never as passionately as now.

The soldiers in this war of words represent two distinct camps: the carb army, who argue that elite athletes should focus on high-carbohydrate diets; and the fat army, who believe fat should be the athlete’s main source of fuel.

In the so-called diet wars, scientists take polarised positions on what works best, often engaging in public spats on social media.

“Not only are there battles on the sports field, there are battles in sports science, and they can often be brutal,” says Professor John Hawley, director of ACU’s MacKillop Institute for Health Research, adding that diet is “a horribly emotive topic”.

Professor Hawley and his wife Louise Burke, an ACU professorial fellow and the long-time head of nutrition at the Australian Institute of Sport, are among the world’s leading researchers in the field.

In a comprehensive review published in Science, the duo found that different tactics work depending on the sport, the phase of training and the athlete’s individual experiences with a nutritional strategy.

While modern-day athletes are “bombarded with social media ‘warriors’ who evangelise vegan, paleo and low-carb ‘keto’ diets for peak performance”, Burke and Hawley argue against an enduring belief in a single, superior “athletic diet”. Instead, they favour diversity in dietary practices.

But alas, everyone loves a good fight. So when the New York Times published an edited interview with Professor Burke on the review’s findings, dozens of partisan punters weighed in with either a pro-fat or a pro-carb slant.

Professor Burke responded swiftly, expressing regret at the fact that sports nutrition had been “reduced to a war where you have to choose to be on 'the fat army' or 'the carbohydrate army’.”

She concluded with some self-directed advice: “Note to self: Never use the words ‘high-carb diet’. We need more-precise terminology …”

Despite their refusal to choose a side in the diet wars, Burke and Hawley’s Science article declared carbs were the go-to fuel source for most sportspeople.

“When elite athletes train for and compete in most sporting events, … the availability of [carbohydrate], rather than fat, wins gold medals,” the review says.

There are, as always, exceptions to the rule.

For athletes who compete in very long, relatively low-intensity events like ultra-marathons, a diet that is high in fat and low in carbs could be beneficial.

Leading long-distance runner Zach Bitter trains and competes with carbohydrates accounting for as little as five per cent of his diet. He claims his performance and general wellbeing have improved since switching to a high-fat ketogenic diet.

“There are ultra endurance events — and I am talking about things like running across America or 100-mile races — for those events, fat adaptation is probably a very good thing,” Professor Hawley says.

“The reason for that is that these events are undertaken at such a low intensity that oxygen is freely available, and when oxygen is available, fat is not a problem to burn.”

Even then, many ultra-endurance athletes add carbohydrates to the fuel mix for races and some “high-quality” training sessions. “It really is about switching around fuel sources according to the demands of the session,” Professor Burke says.

In recent years, Burke and Hawley have conducted several studies examining the effectiveness of high fat, low carb diets for elite athletes.

“I’ve seen it come and go three times in my lifespan as a sports dietician and I invested a good decade of my research life trying to make it work,” Professor Burke tells Sports Illustrated.

Her research has shown that when training or performing at a higher intensity, a high-fat diet could actually impair performance.

Even long-distance events like marathons and road cycling rely on high rates of carbohydrate availability, both throughout the event and during key moments when an extra burst of energy is required. Take four-time Tour de France winner Chris Froome, whose success has been attributed to a fuelling strategy that sees him consume the equivalent of 85 slices of bread on race day through a high-carb sports drink.

Burke and Hawley argue that fat cannot replicate the high-octane performance benefits that carbohydrate provides.

“If fat worked, we would be doing it,” Professor Hawley tells Impact. “There is no hidden agenda here. We are not averse to high fat diets, but the bottom line is, there are very few events on the Olympic calendar where you can say fat is the defining source of fuel for success.”

For her part, Louise Burke can definitely lay claim to knowing what it takes to prepare sportspeople for athletic success. For almost three decades she has been the chief architect of the sports nutrition program for elite athletes at the Australian Institute of Sport.

Meanwhile, Professor Hawley is one of the world’s leading exercise physiologists; his research focusing on the role that fat and carbohydrates play in performance.

“What we are saying quite clearly is that different sports have different demands, and we are not anti-fat or pro-carb, but for the majority of events that are done in under three hours, carbohydrate will be the predominant fuel preferred by muscle,” he says.

“Any time you are out of breath, your muscle will opt for carbohydrate as the most efficient fuel.”

The enduring carbs versus fats debate could be partly explained by the emergence of evidence challenging the paradigm of “all carbs, all the time”.

In the past decade, repeated studies have shown that both fats and carbs could be utilised for optimal performance and recovery.

This move towards “periodised nutrition” focuses on fuelling for the work required, making the timing of carbohydrate consumption crucial to peak performance.

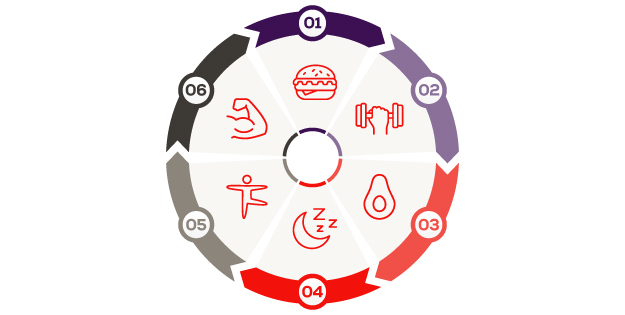

In their review, Burke and Hawley detail the evidence backing the “train high, sleep low” strategy, where the athlete loads up on carbohydrates at lunchtime to fuel their high-intensity workout that afternoon. After depleting their body of carbs, they consume a high-fat, low-carb dinner before overnight rest and recovery (hence the term “sleep low”). Next morning, they complete a longer, lower intensity workout on an empty stomach and then stock up on carbs so they can “train high” again that afternoon.

But while periodisation is increasingly popular amongst modern-day athletes, personalisation is just as important, Professor Hawley says.

“When it comes to nutrition, different things work depending on timing, but I would extend that to say that different things work for different people, and also, different people work differently,” he says.

Kenyan distance runners serve as an example of a group that dominates their sport despite having a diet that often clashes with athletic guidelines. However, we don’t know if their success is because of, or in spite of, their nutritional practices, and it’s likely that genetic and environmental factors are also at play.

“If you were born at altitude and weigh 53 kilograms wringing wet and you've run to school all your childhood, then you've probably got an advantage regardless of your nutritional strategy,” Professor Hawley says.

“So yes, their diet differs from most athletes and yet they still perform well, but what happens if you take a European and transpose them into Kenya or Ethiopia on the same diet? I have no doubt they would have problems.”

Hawley and Burke are strong believers in the power of science to help sportspeople maximise their athletic potential.

But they don’t seem to hold out much hope of a scientific consensus in the diet wars. In a recent study examining the effect that carbohydrate and fat can have on athletic performance, Professor Burke and her co-authors concede that sport scientists would “continue to hold different views” on the best way to prepare athletes for optimal performance.

However, it’s not only scientists who hold strong positions on this topic. Elite athletes, recreational sportspeople and even armchair critics have been known to engage in flame wars on sports nutrition.

The odd thing about this battle is that, at least in the case of scientists, the combatants are often colleagues and friends.

One of the world’s strongest advocates for high-fat diets is Professor Tim Noakes, who has over the years collaborated with Hawley and Burke on many studies and even wrote the foreword to their 1998 book Peak Performance.

Noakes stunned and alienated many academic colleagues when he back-flipped and started promoting a high fat diet as the key to fitness and health, labelling carbs as an addiction that poses severe health risks.

“I find both the message and the delivery style disappointing,” Burke tells Outside Online. “Very few issues in science have a polarised, one-size-fits-all truth. Insisting on this … often misrepresents where the scientific knowledge has actually evolved to.”

At the very least, Hawley and Burke hope their review convinces athletes to look for “bespoke solutions” that are tailored to their sports, their competitive goals and their individual responses to nutritional strategies.

And while they’re keen to showcase the contributions science has made to gold medals and world titles, they concede that many lessons “have also flowed in the opposite direction”.

“It’s true that in many cases athletes have changed our thinking and taught the scientists something — it’s a two-way flow of information — and that is why we stress the importance of an individualised approach that uses a combination of science-driven advice, and trial and error,” Professor Hawley says.

“There is no such thing as ‘one science fits all’.”

John Hawley and Louise Burke represent ACU’s Mary MacKillop Institute for Health Research, which brings national and international experts together to undertake research that discovers effective strategies to create a healthier Australia.

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008