Study

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

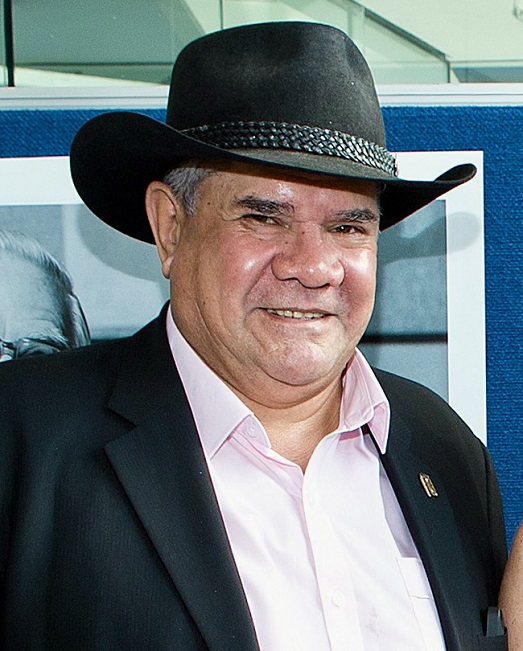

In the early 1970s, when Mick Dodson was on his way to becoming the first Aboriginal man to graduate with a law degree, Indigenous issues barely got a mention in the curriculum. This was a time of great activism and change, with Aboriginal legal services being established all over the country, and the powerful land rights movement gaining pace.

And yet, in Australia’s law schools, discussions on Indigenous matters were so rare that Dodson can clearly recall the day a lecturer mentioned the ground-breaking Gove case, the first-ever litigation on native title in Australia.

“I studied at a brilliant law school with lots of young and innovative lecturers and tutors, but in a five-year course, it was the only case we ever discussed that had something to do with Aboriginal people – and the discussion was over in two minutes,” says Professor Dodson, a member of the Yawuru people of Western Australia, who joined ACU’s Thomas More Law School in 2023.

Even as an undergraduate, Dodson was no shrinking violet, so he cleared his throat and raised his hand.

“It was a full lecture theatre and I was one of only two Indigenous students in the class, so it was either really brave or really stupid of me,” he recalls. “But I’d like to think it was the former, because by speaking up, I managed to significantly extend the discussion on what was a crucial case in the history of land rights in Australia.”

That courageous young student would go on to become one of the country’s foremost Indigenous lawyers.

Over a long and impressive career, Professor Dodson, 74, has combined legal practice with diplomacy, leadership and academic research to fight for the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, representing their interests on a range of issues including reconciliation, native title, and constitutional recognition.

But he makes it clear that he is not one for “big-noting” himself.

When asked to reflect on his achievements, he hesitates, saying there are “plenty of others who have worked just as hard as I have but have received very little recognition”. Even the entry for the Australian of the Year award he received in 2009 describes him as “humble”.

It is worth noting, however, that his many accomplishments are a triumph over the tragedy he experienced in his childhood.

When his parents died months apart when he was 10, Mick and his four youngest siblings became wards of the state. They were in grave danger of being permanently separated from family until their older sister, aunt and uncle won custody, eventually helping Mick and his brother Patrick to secure scholarships at Monivae College, a Catholic boarding school in Victoria.

The transition was “not a piece of cake”, and the boarding school was “a bloody tough place to grow up”, but Dodson soon proved a standout, thriving in sport and academically and being voted by his peers as house captain and prefect.

He says he feels fortunate to have received a good education at Monivae.

“I certainly learned a lot,” Professor Dodson says. “It opened up opportunities and gave me access to knowledge.”

That said, he remains conscious that many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children struggle to grasp such opportunities.

While progress has been made, Indigenous students still contend with tired stereotypes, he says, and are often stalled by watered-down expectations. This can make their experience of school an overwhelmingly negative one.

“Within Indigenous families, there is a living memory of education as an instrument of disempowerment, dismantling languages, cultures and traditions,” he says.

“We have to realise the lasting impact of colonisation on all Indigenous societies in Australia. It’s a complicated and destructive thing to happen to any society, and there’s been a generational transfer of the pain and hurt and agony. It’s not like you can take a Panadol and get over it.”

It’s now some five decades since Mick Dodson graduated from law school, and Indigenous-related content is much more prevalent in Australian legal curricula.

But there’s still work to be done.

Since joining ACU in a part-time research role in late 2023, Professor Dodson has been focused on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander legal research and knowledge formation, with a central task of redeveloping the law curriculum through an Indigenous lens.

“That means being prepared to weave the Indigenous viewpoint and experience into what’s being taught,” he says.

The aim of the project is twofold: to improve opportunities and outcomes for Indigenous law graduates, while also supporting non-Indigenous graduates to develop cultural capability and awareness, enabling them to work effectively alongside Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities.

“We still get young law graduates going into Aboriginal legal aid or working with an Indigenous corporation of some sort, and many of them know very little about Aboriginal culture and laws, about spiritual and cultural traditions, kinship rules, and ways of doing things – and that can be a real shell-shock,” says Professor Dodson, whose first job out of law school in the 1970s was with the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service.

“One of the things I would hope we could achieve at ACU is to reduce that shell shock, so that law graduates come out ready and informed, with a better understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societies, and the capacity to represent Indigenous individuals or groups.”

Despite the efforts of law schools to embed Indigenous knowledges and perspectives into curricula, he believes “the content is still a major issue”.

“There needs to be more in the curriculum that considers the role of Indigenous law and custom, which is thousands of years old, as well as the role of British law in the dispossession of the original inhabitants,” says Professor Dodson, adding that the shortcomings in the curriculum can drastically affect the experience of Indigenous law students.

“The silence on Aboriginal issues when I was at law school was deafening, but that was a long time ago, and since then, the number of Indigenous people studying and graduating law has exploded. These students can’t help but feel the absence of their voices, and it’s well past time that we made a change.”

Mick Dodson AM is a Professor at the Thomas More Law School, working on Indigenous legal research, knowledge formation, and curriculum development through an Indigenous lens. He was Australia’s first Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner with the Human Rights Commission.

He has made many contributions to human rights, social justice, and Indigenous affairs in Australia and around the world.

Learn more about ACU.

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008