Global

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

A generous auntie scours the toy aisles for an impromptu gift for her niece and nephew. She comes across a bright pram and doll set (a perfect present for her niece), and spots a crazy science experiment kit (a great gift for her nephew), and her shopping is done.

What the generous auntie doesn’t realise is that her good-hearted gifts may have an unwanted side effect: they could reinforce some problematic gender stereotypes to her beloved niece and nephew.

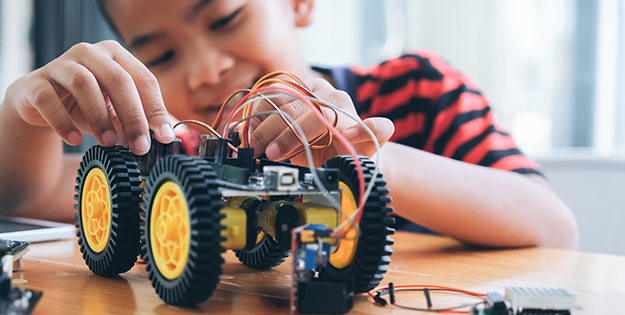

These society-fuelled tropes (where science and construction-related toys are marketed to boys, and dolls, cleaning and kitchen toys are marketed to girls) tend to influence children’s beliefs at a young age, limiting their choices and leading them to aspire to “traditional” male and female jobs.

“What we’re finding is that kids are still coming into early schooling with preconceived ideas about what it means to be a girl or a boy,” says ACU’s Laura Scholes, Associate Professor at the Institute for Learning Sciences and Teacher Education.

“So they bring these societal beliefs that they’ve picked up from toys, adult family members and media, and when they get to school, the schools aren’t actually challenging these ideas – in fact, they’re probably making them stronger by the way girls and boys are treated at school.”

In a recent study that explored the role of gender stereotypes in career choice, Scholes and her co-author Dr Sarah McDonald asked 322 Year 3 students from 14 Australian schools a series of questions about the types of jobs they want in the future.

The researchers discovered that an alarmingly small number (6 per cent) of the girls interviewed aspired to a career in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. In contrast, around one in five boys (22 per cent) hoped to pursue a career in these fields.

These findings were an unwelcome surprise, given the well-known fact that Australia’s talent pool is limited by the underrepresentation of half of the population – girls and women – in STEM education and careers.

They also come amid sustained government campaigns to get girls interested in these subjects, indicating a stubborn persistence of the gender gap in STEM aspirations.

“Given that the focus on engaging girls in STEM has been ongoing for some time now, we would’ve expected that more girls were aspiring to work in the science and technology fields,” says Associate Professor Scholes, whose research explores gender stereotypes and schooling.

“The fact that girls still aren’t expressing an interest in these fields shows that we need to get in earlier, and to be much more sensitive to the belief systems children have at this early age.”

The “get in early” message is incredibly important, Scholes adds, because the careers children are thinking about at school “are a good indication of the jobs they will pursue in adulthood”.

In their study, Scholes and McDonald contend that traditional constructions of gender – where “tough” men and boys are attracted to power and control, and “nice” women and girls are focused on caring and passion – are still relevant in modern-day Australia.

The top three career choices for boys in the study were professional sports, STEM-related jobs, and policing or defence; the girls, meanwhile, were drawn towards teaching, working with animals, and careers in the arts.

“The girls were very much interested in caring and helping others, and having that sense of love for their occupations,” says Associate Professor Scholes, who adds that these were the same jobs girls were attracted to 20 or 30 years ago.

On the other hand, the boys’ career choices heavily featured “masculine” themes: making money and wielding power, and jobs that indicate strength, dominance and physicality.

Scholes and McDonald suggest this could partly be a result of Australia’s history of “laddish cultures”, and “narrow boundaries around what it means to be a man and subsequently what it means to be a boy at school”.

This can be seen in some of the justifications that boys gave for their career choices. Many of them talked directly about power and persuasion.

“I am good at arguing and I like it,” said a boy who aspired to be a lawyer.

“I can kill people,” said a wannabee assassin.

“I can put people under arrest,” said a budding police officer.

“I get to do what I want,” said an aspiring president.

The girls cited much gentler, more altruistic reasons for their attraction to a particular line of work.

“I want to be a teacher because I love little kids,” one student said.

“[I want] to help people if they get hurt and take care of my dad and people,” said an aspiring nurse or doctor.

“I like to help people or animals,” said a girl who’d like to be a nurse or a vet.

While gender clearly influenced the choices of the children interviewed, social class also played a role.

Almost one in three boys from affluent school communities aspired to a career in science, technology, engineering and mathematics, while fewer than one in 10 underprivileged boys were interested in STEM.

Meanwhile, girls from disadvantaged schools were more inclined to opt for jobs with the “feminine” ideals of caring and helping. While this did include some STEM roles, they tended to be in the medical and life sciences, rather than high-growth careers in computer science and engineering.

And as Scholes and McDonald point out, the gender gap is particularly high in these fast-growing and well-paid jobs, which are tipped to dominate the future workforce.

So, what’s the key to addressing old and outdated ideas about the role of women and men in society?

The first step, says Associate Professor Laura Scholes, is to challenge these potentially problematic beliefs.

“I think it starts at home with the parents, and when kids get to school, it’s really important that we act quickly to challenge some of the preconceived ideas they might have brought with them about gender roles,” she says.

“At a practical level, that means teachers need to get in there and open up discussions, and to ask them: ‘What does it mean to be a boy or a girl? What are your options?’

“It’s not about forcing them into science or engineering if they’re not interested in those things, it’s about broadening options and experiences while they’re young, before they get too limited.”

Scholes and McDonald suggest that policy agendas that disrupt norms and widen participation need to start early in life.

One way of doing this is to provide so-called “communities of practice” in early primary school classrooms, where young boys have the opportunity to be caring and nurturing, and girls are given the chance to look beyond these traditionally feminine ideals. This needs to take place in a safe environment where alternatives to stereotypes are made visible.

There are also moves to get real-world examples of female scientists and engineers into schools, as a way of broadening the horizons of young students.

“It’s really all about challenging norms,” says Associate Professor Scholes. “So rather than accepting the narrow idea that girls want to be carers and boys want to wield power, we’re broadening their ideals and giving them more options.”

And what about our generous auntie, who followed societal norms and bought her niece and nephew the typical gendered toys? After all, research has shown that toys can give young children the wrong ideas about gender roles.

While recent moves by toy manufacturers to avoid reinforcing harmful stereotypes may be helpful, it again comes down to opening discussions – with children and adults alike.

“It’s about being open about the effect that these norms can have, and perhaps thinking more deeply about the possibility that we’re exposing children to messages that can reinforce certain stereotypes,” Associate Professor Scholes says.

The end goal is to move away from the idea that only certain toys or modes of play – and therefore certain career choices – are acceptable for boys and girls.

“If a boy wants to play in the home corner, that’s okay, and if a girl wants to play with trucks, that’s great, too. Let’s let girls be scientists and boys be carers, if that’s what they want.”

Laura Scholes is an Associate Professor researching gender and literacy at ACU’s Institute for Learning Sciences and Teacher Education. She is a Principal Fellow of the Australian Research Council, researching how to challenge masculinities associated with boys’ failure in reading.

Explore the courses available at ACU.

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008