Global

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Over a decade ago, literacy expert Genevieve McArthur took a phone call from a distressed mother whose son was not only struggling with reading at school, his emotional health had also begun to spiral. Given she was not an expert in mental health, she decided to scour the research evidence to find some guidance on what the mother could do – but the search failed to yield a clear answer.

Instead, Professor McArthur discovered that studies assessing the mental condition of children with reading difficulties were few in number, and many of those that had been done were poorly designed, meaning the findings were unreliable. Worse still, there appeared to be no evidence-based interventions aimed at helping poor readers who also had mental health problems.

“You had clinical psychologists focusing on mental health problems in children, and you had literacy experts focusing on reading problems in children, but neither understood the other side of the equation well enough to be aware of the methodological intricacies of studying both of these problems at once,” says Professor McArthur, who joined ACU’s new Australian Centre for the Advancement of Literacy (ACAL) in 2023.

In the years that followed, as Professor McArthur continued with her research on reading difficulties, she and her colleagues encountered more and more parents seeking help for their children who were struggling with both reading and mental health.

“Families would say, ‘I used to have a child who was as happy as Larry, and when they started school and realised they couldn’t read as well as their classmates, they withdrew and became unhappy’,” she says. “These parents would ask us, ‘Do you think these two things could be related?’”

It got to the point where Professor McArthur and one of her PhD students – Deanna Francis, who is now a postdoctoral research fellow at Black Dog Institute – decided they would have to do more to understand what was going on.

“It was still not clear to us if there was a genuine association between poor reading and emotional health, why this might be the case, or how these problems might be alleviated,” she adds. “It was well beyond time that somebody started to find answers, and we had arrived at the point where if nobody else was doing it, we were going to have to do it ourselves.”

In recent years, experts from around the world in both reading and emotional health have started to work more closely to better understand if and how reading difficulties and poor mental health are related in some children.

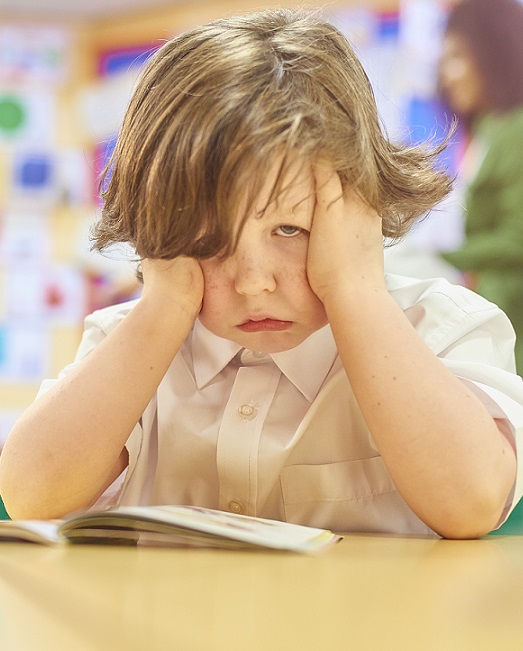

At this point in time, the findings of their research suggest that if a child starts to fall behind their class in learning to read, they may start to receive negative feedback from their teacher, their classmates, or even themselves. This may start to affect their self-concept for reading, thereby causing them to feel worried and anxious about reading – particularly in front of other people.

“Anxiety is an awful thing to experience, and it’s extremely difficult for children to push themselves through doing something, particularly publicly, that they don’t believe they’re good at,” says Professor McArthur, who explored the relationship between poor reading and emotional problems in a commentary for The Conversation.

“It’s the equivalent of asking somebody to stand on stage in a concert hall and play an instrument that they don’t know how to play, which is the kind of thing people have recurring nightmares about.”

Quite understandably, some children do what they can to avoid feeling anxious by skipping lessons, asking to go to the bathroom, or zoning out during class. Alternatively, they may become so anxious that they simply cannot concentrate on their lessons – no matter how hard they want to.

Either way, they receive less reading instruction than other children and fall even further behind. This further impacts their reading self-concept, reading anxiety, and reading engagement, triggering a vicious cycle between their reading and their mental health.

There are two ways we can tackle this negative cycle. For children who already have problems with both reading and mental health, the science suggests that the best option is targeted and intensive intervention by trained professionals.

For example, in a 2021 study, a group of Australian primary school children were given 12 weeks of intensive and targeted treatment for reading and anxiety and showed significant improvements in their symptoms.

This followed another Australian study, published in 2020, which delivered reading self-concept training to 40 children with reading anxiety. Many of the students involved improved their coping skills, forgoing avoidance and procrastination and instead opting for more positive strategies.

Meanwhile, the Black Dog Institute is currently trialling a novel intervention for anxiety designed specifically for children with reading difficulties. Grounded in the principles of “exposure”, which is a component of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, this online digital intervention aims to avoid the text-heavy nature of many other anxiety therapy programs, which are unsuitable for children with reading difficulties.

For children who are just starting to struggle with reading in the classroom, the best option is prevention. Very little research has investigated this option. However, it is possible that teachers could play a critical role in preventing – or at least minimising – children developing poor reading self-concept, and hence reading anxiety, in the first place.

In collaboration with ACAL’s Dr Tina Daniels, Professor McArthur aims to design a program that can help educators identify those at risk of reading anxiety early on.

“Can reading anxiety be prevented? It’s a big unknown for us at the moment, and we want to get a better understanding of what opportunities we might have in the classroom at that very point when the teacher and the child both realise that the child is struggling with reading,” she says. “If we can catch these kids at that very moment, it’s possible we can intervene before the negative cycle is triggered.”

As for the mother whose phone call sparked Professor McArthur’s interest in this topic, she and her son had a happy ending. Once the boy found an activity he was good at, he began to define himself by his success rather than his reading difficulties, helping to break the negative cycle.

“That experience has stuck in my mind not only because it was a happy outcome, but also because it was a lucky one – and scientists generally don’t like positive results based on luck,” Professor McArthur says.

“If we’re going to make real inroads, we need to keep doing studies, gathering the evidence and building on the momentum we currently have … hopefully we can hit this problem from both the preventative side and the intervention side, and do something good to help children, families, and teachers to tackle this issue.”

Genevieve McArthur is a Professor at ACU’s Australian Centre for the Advancement of Literacy. Her research focusses on reading and language difficulties in children, and how they relate to emotional health. She advocates for the rapid translation of scientific knowledge into real-world practice.

Learn more about ACAL’s research and strategic priorities.

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008