Global

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

When one pictures the massive influx of European migrants to Australia after the Second World War, they see Italians, Poles, Yugoslavs and Greeks, all invited here to help the nation meet its acute labour shortage at the time. But among them were the ‘White Russians’ — a sizeable group of refugees who were, says ACU historian Sheila Fitzpatrick, “almost totally invisible in Australia’s post-war migration story”.

Remarkably, Australia initially took in the largest number of Russians displaced by the war, although it seems almost nobody was conscious of this inflow. The reason for the obliviousness, says Professor Fitzpatrick, is that Russian migrants had “a habit of concealment”.

“They made themselves invisible by travelling under other national labels, so rather than identifying themselves as Russians or Soviets, they said they were Poles or Yugoslavs or some other nationality,” she says.

“They preferred to keep a low profile for fear of trouble, and because they felt vulnerable to the Soviets finding them and trying to force them back to Russia.”

With the Cold War brewing, Australia and its allies fretted over the ‘Red Peril’, the threat emanating from communist states like the now-dissolved Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

But who, then, were the White Russians?

“That’s a complicated question, because among Australia’s post-war migrants, we had all kinds of Russians and former Soviet citizens,” says Professor Fitzpatrick, a researcher with ACU’s Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences.

“We had not only ethnic Russians but many others as well … Ukrainians, Belorussians, Uzbeks and other ethnic groups, all of whom may fit under the word ‘Russian’. And, in addition to the Russians coming from Europe, we took in an equally large group of Russians who had spent the interwar years in China.”

In the simplest terms, however, White Russian is a political denominator. They were, Fitzpatrick says, “the ones who weren’t Red Russians”.

“Anti-communism was the political persuasion they embraced,” she adds. “It formed a visible bond among the Russians who came to Australia after the war.”

As one of the world’s leading scholars of Soviet history, Sheila Fitzpatrick has long been interested in modern Russia.

A daughter of the historian and journalist Brian Fitzpatrick, she attended the University of Melbourne and decamped Australia in 1964 to pursue her doctorate at Oxford.

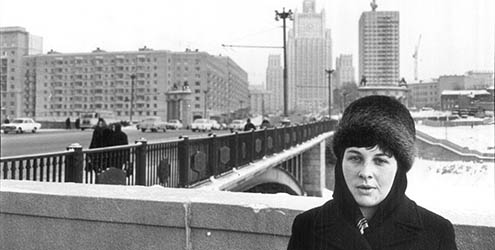

Sheila in Moscow as a graduate student in the late 60s.

As a talented and inquisitive early-career historian, she headed to Moscow, where she gained access to the official archives and broke new ground on the West’s understanding of the USSR. She’s been described as “a trendsetter” who challenged the traditional approach to Soviet history, catapulting her to “fame and controversy” and landing her a distinguished academic career in the United States.

Much later in her career, with a return home imminent, she began for the first time to dig into Australia’s interactions with the USSR.

“I’d been a Soviet historian for a very long time and spent many years overseas,” says Professor Fitzpatrick, an honorary fellow of the Australian Academy of Humanities.

“In the years leading up to 2012, I’d been visiting Australia and also going to Russia to work on their archives, and I stumbled on some terrific material relating to these displaced Soviets. I was both astonished and delighted.”

This sparked her interest, and in the years that followed, she initiated a major research project exploring the Russian migrants who settled in Australia after the Second World War.

The result is the fascinating book White Russians, Red Peril, published in early 2021 to wide critical acclaim.

While several Australian historians have delved into the nation’s Displaced Persons scheme, which between 1947 and 1954 brought some 170,000 refugees here from Europe, few have looked into the Russians in such detail.

Through painstaking research, Professor Fitzpatrick was able to ascertain that at least 20,000 Russians came here from Europe and China in the decade after the end of the war — a number much higher than the official records show.

She drew on a variety of sources for the project, including reams of archival material, and a large body of oral testimony through interviews with dozens of Russian-Australians and officials.

Her research brought her to the understanding that being Russian in Australia at the time could be difficult for more reasons than one.

As is pointed out in White Russians, Russia’s association with communism “had a longstanding linkage in the Australian imagination”.

Despite the fact that most Soviet migrants were “strong and even vehement in their anti-communism”, there was still a “popular and official suspicion that, lurking in every Russian, there was something Red”.

“This was the irony of the situation, because first of all, most of these people who came here were genuinely strongly anti-communist,” Professor Fitzpatrick tells Impact.

“The second thing is, in order to get selected by our migrant selection committees, you really had to say you were anti-communist, otherwise we wouldn’t take you. That introduces a note of doubt, and that fact is that Australia was quite suspicious and worried about getting anybody of communist sympathies.”

To a degree, the suspicion was justified. In Sydney, Russian communist sympathisers even had a hang-out: the Russian Social Club. This left-wing, pro-Soviet club was a stone’s throw from the anti-Soviet Russian House.

“The members of these clubs would exchange insults quite freely,” says Professor Fitzpatrick, who points out that although neither club had a liquor licence, the alcohol flowed in both houses.

Sheila and friends at the Strathfield Russian Club in 2015.

Relations between members of the clubs were frosty. Fistfights in the street were commonly reported, and the friction created wider discord in the community.

There was, however, one thing that bonded Australia’s Russian community: the Orthodox Church.

“The Church really became the force that tied the community together,” Professor Fitzpatrick says, clarifying, however, that it excluded Russian Jews, who went on to form a separate community.

“It was the underpinning for a range of cultural activities, including Russian language schools for children, male and female choirs, and charities.”

Sheila Fitzpatrick describes White Russians as, first and foremost, a migration story.

“Not the benign kind … in which people look to better their situation by moving to a foreign land, but the desperate kind, in which refugees whose lives have been overturned by war and other disasters take a leap into the unknown …”

Most of the Russians who made Australia home weren’t concerned with politics and in-fighting; rather, they busied themselves with life in a new country, often under difficult circumstances.

In some cases, families were torn apart as men were sent off to fulfill their two years of work obligations, while women and children stayed on in migrant camps or moved to the city.

Children dealt with schoolyard racism, including the taunt that “DP means dirty pig”, and adults found that Australians, while not actively hostile, were “fundamentally indifferent”. When the DPs spoke Russian, the locals “simply cursed and shouted, ‘Speak English!’”.

For Professor Fitzpatrick, the book also has a personal connection. Her late husband, the renowned physicist Michael Danos, was himself a Russian-speaking Latvian migrant displaced by war, and was the subject of her memoir Mischka’s War.

In White Russians, she writes that ‘Misha’ was “the person who first made the experiences of war and migration, with all their complexities, real to me in human terms”.

Russian church in Seven Hills and Strathfield Cathedral of Peter and Paul, Sydney.

“After Misha died, I went through his papers and found this really interesting stuff, and so the project of writing Mischka’s War and my return here to Australia were the two main things that drew me to migration history,” says Professor Fitzpatrick, who enjoys researching the topic in part for its air of mystery.

“I suppose I’m interested in the Russians because, as a scholar, I like things that aren’t too straightforward. There’s a lot of ambiguity about their claims, and who they really are.”

Her research now has two parallel streams — the work that she’s most known for internationally, as a leading Soviet historian, and her newer work on migration, which she’s becoming known for in Australia.

But what about current-day Russia, and the long reign of President Vladimir Putin? Is that something she takes an interest in?

“Well, anybody who works on Soviet history tends to automatically answer that question by saying, ‘No, no, no, no. Don’t ask me about the politics. I’m staying out of that.’”

However, her next book, The Shortest History of the Soviet Union, which will be published by Black Inc in March 2022, not only gives an overview of the Soviet age, but also its afterlife under President Putin.

“I guess I surprised myself, because I found writing about Putin very interesting,” Professor Fitzpatrick says.

“From the very beginning, my interest in Russia happened by accident, and I think that tends to happen a lot in one’s career. So as for what happens from now on, I guess you never know.”

Professor Sheila Fitzpatrick is a historian with ACU’s Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences. She was based in the United States for many years, latterly as Bernadotte E. Schmitt Distinguished Service Professor at the University of Chicago, before her return to Australia in 2012.

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008