Community

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

How art can ease the tension around death and dying and help us come to terms with our own mortality.

There’s a saying in Bhutanese folklore that the happiest people are those who contemplate their death at least five times a day.

That might seem over-the-top or even morbid to some, but the wise men and women of Bhutan are not alone in advancing the idea that there are benefits to contemplating death.

Artists from around the world have long used their art to reflect on and grapple with their own mortality.

The subject has been at the centre of the art of Catherine Bell, a multi-disciplinary artist whose work spanning almost three decades has explored death and dying.

“Death isn't something that scares me,” said Associate Professor Bell, visual art lecturer at ACU’s School of Arts in Melbourne.

“Obviously there’s a lot of anxiety around it, but my exposure to it from a very young age helped me to understand it is a normal part of life.”

Bell was first confronted with death as a child, when her grandfather died from skin cancer. At the time, death literacy was not very advanced — “there was definitely a taboo around talking about it, especially to children” — but despite being shielded from her grandfather’s funeral, his death triggered something in her.

“For a very long time this contemplation of death has been ever present, and it fuels my motivation to live a productive and fulfilling life,” she said.

While in high school and later as a university student in Queensland, Bell worked in a series of internships and jobs in healthcare settings that gave her further exposure to different communities facing death: babies with cystic fibrosis, elderly veterans, AIDS patients, women in palliative and aged care.

“Not many people have that experience in their teenage years, and I guess it was quite eye-opening, but that firsthand exposure didn’t frighten me,” she said.

We Die As We Live exhibition at St Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne.

This closeness with death, and the passing of her father while she was pursuing her PhD, prompted Bell to explore the topic in her artwork. She sees art as “a vehicle to challenge taboos and discuss the undiscussable”.

“I think of myself more as a cultural anthropologist, because if I see a problem in society — like the fact that we don't confront the reality of death or give people the opportunity to talk about it — then I feel my job is to facilitate artistic forums to provide a safe space for that discussion to occur,” she said.

Bell has spent much of her recent career trying to provide those safe spaces.

In 2012–13, as part of a long-term artist residency at the Caritas Christi Hospice in Kew, she worked in partnership with palliative care patients to construct Flower Tower, a four-metre high sculpture featuring hundreds of handcrafted paper flowers.

Bell said she learnt a lot about death by observing how participants saw flowers as a metaphor for their own lives.

“As the petals fell off, they would compare that to their physical decline, and making the flowers as a group helped them to feel comfortable to talk about death and say things they might not have been able to say to their family members,” she said.

''That was one of the epiphanies of collective artmaking in the hospice setting — that in sharing communal creativity, you're also sharing communal death.”

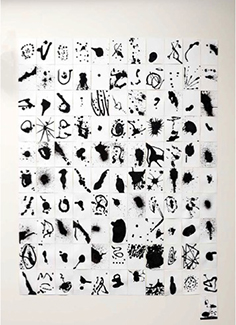

In 2017, she undertook a yearlong research project at St Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne, resulting in the exhibition We Die As We Live, which opened on All Souls Day — a Catholic holy day that celebrates the dead.

This time, her co-creators in the project were palliative care staff including nurses and doctors — people who are confronted with death on an almost-daily basis. Bell saw them as “death elders”, with a deeper understanding of death and dying than most people.

St Vincent’s chief executive Shaune Gillespie described the resulting artworks as “powerful motifs of each participant’s experience of death”, and the participants universally found the creative process transformative.

“It enabled them to discuss the impact that the constant exposure to death has on them, using the marks they made as a tangible prompt to talk about it more freely, and this imagery further stimulated discussion with audiences who saw the exhibition,” Bell said.

“It was really eye-opening to see firsthand how art can be a catalyst for discussing experiences of death that are not normally discussed with perfect strangers.”

The continued tension around the topic of death shows it is still a source of discomfort for many Australians.

An online exhibit produced by the Australian Museum, titled Death: the last taboo, points out that even today, many of us find death frightening and unwelcome.

We still shield our children from the deaths of their elderly relatives, and even amongst adults, death remains steeped in taboo.

There is, however, evidence that the taboo is slowly being busted.

Since 2012, thousands of Australians have attended Death Cafes, places where “people – often strangers – come together to simply enjoy some refreshments while talking about death”.

Furthermore, the medical fraternity actively encourages us to discuss death with our loved ones, arguing that avoiding the topic can have a negative impact on our quality of life.

Associate Professor Catherine Bell tends to agree. And this is where art comes in: for its unrivalled taboo-smashing power.

“Art honours those who have passed and makes these experiences of death tangible; and exhibiting the work opens the conversation up to the public,” Bell said.

Facing Death Creatively Workshops with medical students at Shepparton Art Museum (2019) and artworks made by medical, nursing staff and health professionals at St Vincent’s Hospital and Caritas Christi Hospice, Melbourne.

Facilitating discussion is the main driver for her Facing Death Creatively workshops, where participants mould a miniature vessel out of biodegradable floral foam. The vessel serves multiple purposes: it becomes a portrait of the maker, stimulates personal reflection and group discussion about death and serves as a conversation-starter with family members.

“They take the dust away that has accumulated from making their vessel in a zip-lock freezer bag, talk with their loved ones about where they'd like to scatter this dust, and this starts a conversation about their final resting place,” she said.

“It becomes a rehearsal for letting go, of the fear of death and the physical letting go of the dust. Most people find that quite confronting because even the gesture of scattering ashes causes people anxiety. They get one chance at it and they don’t want to do it wrong.”

Workshop participants send Bell a photo of where they scatter this dust – their desired final resting place – which will eventually form an exhibition alongside the hundreds of individual vessels Bell is accumulating from the workshops.

“This project is my life’s work,” Bell said.

And it’s open to anyone to take part.

“I did the workshop with a group of third-year medical students, healthy 20-year-olds in the prime of their lives, and that was fantastic because it made them think, ‘well, I’m not invincible’, but it also gave them confidence to be able to talk openly to patients about it,” she added.

“After the workshop they continued to reflect on and discuss death, and that’s exactly what I wanted these workshops to achieve.”

And just like the Bhutanese, who often rate highly in the happiness stakes, Bell believes those who regularly contemplate their death tend to lead happier lives.

“I’m using my skills as an artist to promote healthy, meaningful discussions around death,” she said. “It’s really comforting that I can help people from diverse communities to express their fears, anxieties, and unleash their creativity in that way.”

Associate Professor Catherine Bell is a multi-disciplinary artist and curator. She is a visual art lecturer and gallery director at ACU in Melbourne. Her recent research in art and health complements her art practice, which focuses on activism, community engagement and feminist perspectives.

Passionate about art? Explore creative arts at ACU.

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008