Community

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Some two and a half decades ago, when Johanna Harris was studying ancient history at the University of Sydney, she developed a fascination with letters – the hand-inked correspondences that are often dismissed as mere personal exchanges, but which also represent a legitimate form of literature.

Born into a family of historians, Johanna always imagined she would follow in their footsteps. Her newfound interest led her down an unexpected path.

While exploring the letters of Cicero, the great Roman statesman whose work spanned the period from 68 – 43 BCE, she began to see letters as an artform.

“I wrote a thesis on Cicero’s correspondence and discovered a real love of the letter as a literary form,” says Dr Harris, an Associate Professor in ACU’s Western Civilisation program.

“We often think of letters as simply a private and personal mode of writing, but when you go back to those ancient writers like Cicero or Seneca, their letters are very stylised and artful. I found it fascinating.”

In the 25 years since, Dr Harris’s research has explored the literature, religion, and politics of the early modern period, with a particular interest in both letters and epistolary fiction – novels told entirely through the voices of letter-writers and their recipients.

Her publications have focused on the work of celebrated scribes like Andrew Marvell, and lesser-known writers like Lady Brilliana Harley, whose letters offer a rare glimpse into the life of a 17th century woman during the English Civil War.

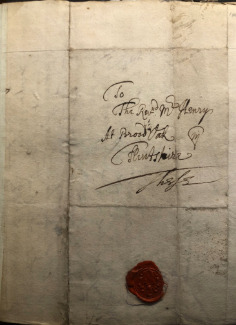

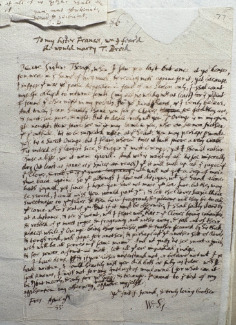

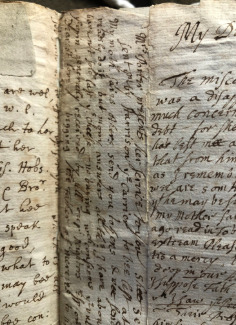

Letters from the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford.

She notes that while relatively few female writers of the period published their work, many were prolific and highly skilled in the art of correspondence.

“Letter-writing was a daily habit for literate women of the time, because in many cases it was their only form of written communication,” says Dr Harris, whose doctoral thesis, completed at Oxford University in 2008, explored Lady Harley’s letters.

“Brilliana left a wonderful collection of around 400 letters, most of which are extant in the British Library, but they hadn’t been studied very much. I wanted to shine some light on them, situating them in their historical context while also evaluating them as literature.”

More recently she has been working on two books investigating the works of puritans and nonconformists like the influential Richard Baxter, who left behind one of the largest collections of letters of any 17th century figure. In early 2025, Dr Harris was awarded the prestigious S. Ernest Sprott Fellowship, allowing her to continue her archival research at the British Library, as well as at Oxford, Cambridge and Manchester.

The letters of puritan writers are particularly fascinating, she says, for the way they intricately combine historical and intellectual matters with spiritual discourse.

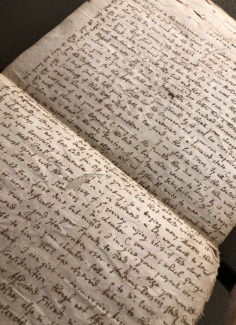

Letters from Dr Harris's archival research at the Bodleian Library.

“For puritans and nonconformists, letters served as a means of thrashing out ideas about politics and religion, and there are many examples of ideas being shaped through letters even before they made it into published works,” she says.

“They allowed the puritans to form alliances and defend this identity, building a sense of community that goes beyond the idea of a letter as a simple means of private communication between one person and another. Letters were often shared around households and communities, which dispels our notion of the letter as distinctly intimate and private.”

This appreciation for literature’s unifying power has also influenced other elements of Dr Harris’s academic work.

During her time as a lecturer at the University of Exeter in the UK, she founded the Exeter Care Homes Reading Project – a volunteer initiative where university students went into local care homes to read with elderly residents.

The project earned Dr Harris a ‘Points of Light’ award from the then-Prime Minister, David Cameron, who praised her vision to provide “valuable companionship and enjoyment to hundreds of people across Exeter”. It also featured in a BBC segment that highlighted the positive effect that literature can have on people living with dementia.

Through the project, which was active for more than a decade, Dr Harris saw firsthand how well-known poems, plays and novels could provide a common link for people from different generations.

“It can be really difficult for younger and older generations to connect and find common ground, and literature can often provide that link,” she says.

“Many of the students were studying the sorts of books or poetry that the residents read when they were at school, and that can create a spark for conversation that sometimes develops into friendship.”

Dr Harris hopes to set up a similar program in Australia, engaging students in the ACU community in the act of shared reading.

“I think anyone who is interested in this kind of initiative should be encouraged to participate, because it helps to build strong links in the community and has clear benefits for both the reader and the listener,” she says. “Literature has a real power to transcend generational gaps and really bring people together.”

When Dr Harris joined ACU in January 2023, she added to the growing list of renowned academics teaching in the burgeoning Western Civilisation program.

The role has given her the chance to move beyond her area of research focus, embracing an interdisciplinary teaching portfolio.

“It’s been exciting for me to guide students as they immerse themselves in the works of literature that have shaped Western thinking, from The Iliad to Shakespeare to Pride and Prejudice, right through to the present,” says Dr Harris, who teaches both undergraduate and postgraduate students in the program.

“It has challenged me to bring my earlier training in history and ancient history and my broad interests in theology together with my main subject area of literature – to think more deeply about the development of different ideas, different styles and different traditions. That’s been incredibly rewarding, and the students are excellent.”

The teaching-focused nature of the role has had another unexpected benefit. It has prompted her to revisit many of the classics she hadn’t read for years.

“Through that process, I’ve started to view these texts in a different light,” says Dr Harris, who recently wrote a piece for The Conversation, titled ‘Why you should revisit the classics, even if you were turned off them at school’.

“Reading these classics with fresh eyes has allowed me to see how much I missed when I first encountered them. Some books you can pick up at different stages of life and they speak to you in completely different ways, and there’s something beautiful about that.”

She finds similar beauty in her favoured form of writing – the hand-inked letters that some refer to as ‘windows to the soul’.

“In the early modern period, there was a real sense that when one received a letter, the reading experience was treated with great care,” she says.

“When geographically separated from friends or family, the letter became a surrogate, carrying the authentic voice of the person who wrote it and bringing a sense of being together.

“It is therefore a literary form that carries a deep sense of meaning and humanity, alongside the crucial ideas that it negotiated. It’s a great shame and loss that letter-writing is no longer as common as it once was.”

Associate Professor Johanna Harris is a lecturer and postgraduate course coordinator in ACU’s Western Civilisation program. Her research focuses on the literature, religion, and politics of the early modern period, with particular interest in non-fictional prose, especially letters, and in devotional writing.

Keen to immerse yourself in the classic books and ideas of Western civilisation? Learn more about the Ramsay Scholarship (worth up to $150,000 each), and the chance to pursue a fully funded liberal arts degree at ACU.

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008