Community

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

For most of his adult life, John Foster has looked back on his childhood with a tinge of bitterness and regret.

“We lived an uncertain life of feast or famine,” says the 64-year-old of his many years as a youngster, performing in his family’s travelling road show.

“On the good weeks, we’d make good money and have fish and chips on a Friday night. Other weeks, eating was a struggle. Dad would cook us up a meal made of bones from the butcher to tide us over.”

Along with his parents and two older sisters, John spent the 1950s and ‘60s traversing eastern Australia in an old truck and caravan, as part of our country’s rich history of circus and carnival performers.

Life on the road meant he had very little contact with children his age, and apart from a few days in Grade 1, he never attended school.

“I saw the kids that went to school as different to me, and I had very little confidence in communicating with them,” says John, whose parents took him on the road soon after he was born.

“That lack of confidence, I think I’ve carried it through almost all my life.”

If the young John Foster did have a comfort zone, it was when he was on stage performing his clowning act.

“When the makeup was on, it was a performance — I knew the act and the words I needed to say to make it entertaining,” he says.

“I’d put on this act of bluff and bravado, this mask of confidence. In reality though, it wasn’t me who was confident, it was the character.”

While many of us joke of running away to join the circus, John can attest that the reality of show business is tough. But it also taught him some valuable life lessons.

“It made me a survivor,” he says, “and looking back, a lot of the time it was a good deal of fun. Nowadays I can tap into the fond memories, but for a long while, I was bitter about the loneliness, about not attending school and things like that.”

Compared with the larger circus shows, which played in big-top tents and travelled with animals and specialist trainers, John’s family road show ran on a shoestring.

His father would cut knives out of sheet metal and scavenge for tree branches and old tyres for making puppets, and his mother would make costumes by hand and paint elaborate signs promoting the show.

“We put the whole thing together out of nothing, out of bits and pieces we’d find lying on the side of the road or in rubbish tips,” says John, who played a supporting role in many performances, including escape-artistry, puppetry and dare-devil acts — not all entirely safe.

The three-year-old John Foster stands at the knifeboard. A few years later, he would stand there for real while his dad threw the knife.

“Dad did knife-throwing and Mum would stand at the board, but one day he got a bit close to her and drew blood,” he recalls. “After that, Mum said, ‘I don’t want to do that anymore’. So Dad pointed at me and said, ‘You’ve been elected’.”

In a dicey sharp-shooting act, John’s father would use a .22-calibre rifle to shoot pieces of chalk and other small items out of John’s fingers.

“Sometimes I’d hold playing cards and he’d cut them in half, and we’d have a metal box with rubber that would catch the bullet,” he says.

“I remember it clearly, the sound of a .22 going off inside a big hall. All the kids would jump and go, ‘wooooh’.”

The kicker? The rifle, bought at a flea market for five shillings, had a bent barrel, and an old nail as a firing pin.

“Dad would have to aim a bit off centre to account for the gun going sideways,” says John, chuckling at the memory.

“It might seem a bit mad, but there was also a lot of humour in it. He was a really good shot and I always trusted him, and not once in hundreds of performances did he ever let me down.”

Some of John’s happiest childhood memories are of him huddled over a book in the family caravan.

While he never had access to formal schooling, John’s mum surrounded him with books. She taught him to read and write and introduced him to the bush poetry of Lawson and Paterson at an early age.

left to right - Sister Terry, John, cousin Frank, sister Carol, Frank's brother in front of Foster family caravan.

“We’d usually camp out of town near a river where we could catch a fish, and that meant we didn’t have much access to electricity,” John says, “so I learned to read and write by candlelight.”

Even this happy memory is streaked with sadness.

“Books carried me through the solitary life that any child feels when they have no friends to play with, and I developed a great love of reading — but it was a lonely love, because I had nobody to talk to about these stories,” he says.

“If I started to talk about literature and philosophy to other kids, they’d get bored or lose track of what I was saying, so I felt like it was better to keep my mouth shut.”

John was still a teenager when the television juggernaut cut a swathe through the road show business, and in 1970, John’s branch of the Foster family threw in the towel. They gravitated towards running carnival amusements on the agricultural show circuit, a business that John stayed in 2014, when he moved to Brisbane.

He made a living and many friends on the show circuit, but he long had the feeling he wanted to do something else. There were strong clues as to what that might be.

“When I was a kid, I’d recite poetry to my family, and I kept doing that into adulthood, often to the annoyance of others — especially when I’d had a few beers around the campfire at agricultural shows,” says John, with yet another chuckle.

“I can see why it was annoying for them, but for me, it was the only way I knew to express my love of the written word.”

While John had a longing to write his own stories, his passion for literature was sidelined by a drinking habit that intensified when he moved to the city.

“It was part of the lifestyle amongst my friends and associates at the showgrounds to drink heavily, and I had abused alcohol most of my adult life,” he says.

“When I left the agricultural shows, I couldn’t go through a day without drinking, and that was out of boredom more than anything. I had made a complete mess of my life and I couldn’t see an obvious future for myself.”

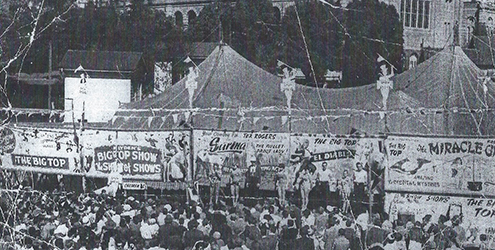

John's grandfather's big top at the Ekka 1963. The Foster family did a sideshow once a year.

It was a health scare that prompted John to give up drinking and turn his life around. Months later, while living in a rundown inner city boarding house, a friend told him about ACU’s Clemente Program, a community-based university scheme that empowers disadvantaged Australians by providing a pathway to tertiary education.

“It just happened to come up at the right time in my life,” says John of the program, from which he graduated in June 2019.

Enrolling in Clemente was a brave move for the former circus performer, who had hardly step foot into a classroom in all of his 64 years. He studied subjects he’d long had an interest in — philosophy, sociology, literature and art — and now plans to pursue a Bachelor of Arts in creative writing at ACU, with a long-term goal of writing a novel.

“Three weeks into Clemente was the first time I’d turned on a computer in my whole life, and at that stage I had only a vague idea of what an assignment or an essay was,” he says.

“It was a crash course in reality, but the support from my lecturers and learning partners meant I never felt alone, and before long I was ready to take on any challenge put before me. I was finally free from the demons that have haunted me for much of my life.”

He even built up the confidence to recite poetry in front of his classmates, without a mask or makeup, or even a hint of bluff or bravado.

“That was a thrill,” says John. “I guess I have a reasonable speaking voice that can capture the nuances of a poem, and some people even suggested I should try acting, but I know that creative writing is my thing.”

That said, it doesn’t take much to convince John to recite a poem. He clears his throat and takes in a deep breath. When he starts talking, his voice has a quiver not previously present, as he delivers Henry Lawson’s The Ballad of the Rouseabout — a piece of writing he can clearly relate to:

“A rouseabout of rouseabouts, from any land — or none,

I bear a nickname of the bush, and I’m a woman's son.

I came from where I camped last night, and at the day-dawn glow,

I rub the darkness from my eyes, roll up my swag, and go …”

Keen to learn more about ACU’s Clemente program? Explore the options.

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008