Future student

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

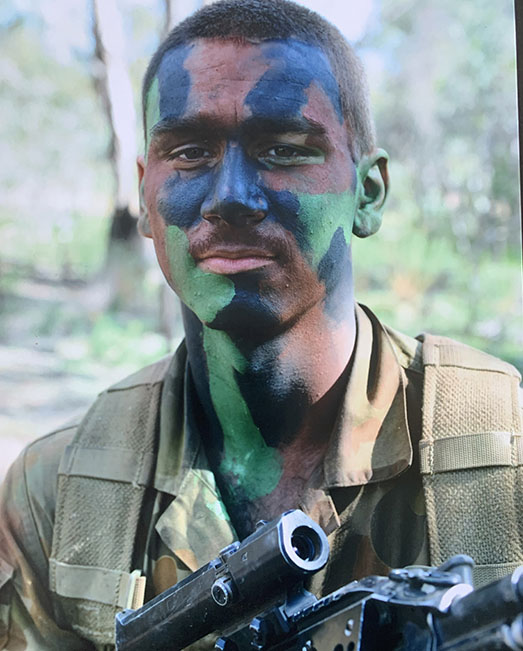

Joel Hartgrove, 29. Wiradjuri man. Hardworking paramedicine student. Keen bodybuilder. One-time party boy who fell into substance abuse and struggled with severe depression. Veteran infantryman who proudly served in the Australian Army. Troubled teen who was shunned by his family and left homeless at 15.

There are many faces to Joel Hartgrove. But most strangers he crosses paths with only see one thing. They see the guy with the tattoos.

“I do find it harder to meet people sometimes,” says Joel, whose face, scalp, neck and ears are adorned with tattoos including a cross, a crown and the words “HAHAHA” on his forehead.

“I think it sometimes just startles people, so they might stare or they’ll actively avoid me or move their children away from me, which is fine. I understand it. It’s not every day you see someone with Joker-inspired tattoos on their face.”

Those who delve beyond the tattoos quickly discover that Joel is an affable and articulate character, a softly-spoken man who’s more than willing to talk about his experiences – the good and the bad.

“I find when people have a conversation with me, they end up generally being surprised,” he says. “More often than not, they’ll say, ‘You’re not who I thought you were going to be’.”

In 2021, Joel gave more people the opportunity to look past the tattoos when he took part in ACU’s Human Library project. During the one-day event, visitors were able to borrow a human “book” and ask as many no-holds-barred questions as possible in 20 minutes.

Joel saw the project as an opportunity to discuss not only his tattoos and the story behind them, but also his struggles with depression and suicidal ideation.

“I’m very open about my life and the things I’ve experienced, because I know what it feels like to hit rock-bottom,” he says.

“It’s a very daunting, vulnerable sort of feeling being down there, and if you have more people around you, people who you feel comfortable to talk to, it can help you to get out of that hole.

“That’s why I think it’s really important that we’re open about these things – it helps to remove the stigma that still surrounds mental health.”

There’s another thing you notice when you have a conversation with Joel Hartgrove: he wears his heart on his sleeve.

Ask him how he came to be homeless at the age of 15, and the warm smile that usually sits on his face quickly fades.

“It’s a bit of a hard situation to explain, actually,” he says, shuffling in his seat.

“Basically one day my mother just sort of said that I couldn’t live at home anymore. I asked other family members if I could stay with them and they all said no. So I ended up homeless, sleeping on mate’s couches on and off for around two years.”

Suddenly forced to fend for himself, Joel left high school and found a job doing the grunt work for an air-conditioning mechanic. Earning money was a good and positive thing, he says, but “the emotional side of pretty much being rejected by your family was pretty bad”.

After a short stint staying with his grandmother, Joel went back to live with his parents for a brief period before moving out once again. He was in his late teens at the time. He’s been virtually estranged from his family ever since.

Years later, in his early 20s, Joel acted on a long-standing passion and joined the army.

In the combat corps, the young infantryman was in his element. “It was awesome. I absolutely loved it. Absolutely loved it.”

Joel was happy to have a secure job and a roof over his head. He liked the training, too; the physicality of being in the combat corps, and the discipline it required. He enjoyed the traditions and ceremonies of the Australian Army, which go back more than a century. But perhaps most of all, he loved the connection he formed with his fellow soldiers.

“It was like a massive brotherhood,” he says. “That was really important to me, especially coming from a place where I had lots of problems with my parents at home, being homeless and not having much support. To be accepted into a massive group and to have so many close friends, it was a really great feeling.”

In the military, Joel had finally found a sense of purpose. And he had no plans to leave.

“It was my dream job,” he says. “I was ready to stay there and that was what I was going to do.”

Then, three years after joining the army, Joel started to notice an intense pain in his back. He left it, thinking it might have been a niggle, but over a period of months, it got progressively worse. He was eventually diagnosed with a series of chronic spinal injuries that meant he could no longer perform his duties as an infantryman.

While the Defence Force was supportive in providing medical support for his rehabilitation, Joel found that the emotional support was lacking – especially from his peers. The brotherhood that had provided him with friendship and a sense of belonging quickly transformed into an army of bullies.

“I faced harassment and bullying from the people who I called my friends, at a time when I was already struggling with the reality of losing my dream job due to a chronic injury,” he says. “I needed support, but what I got was a really toxic environment.”

After he left the army, Joel moved north to Queensland to work with the Department of Housing, a job he enjoyed.

At the same time, his injury and medical discharge triggered a slow but steady spiral into depression.

“It just got worse and worse,” he recalls. “I started drinking more, started partying, and when I made new friends, I made them for the wrong reasons because they just fed into my partying and drinking and all that. From there, my mental health went completely downhill.”

At his lowest ebb, in late 2018, Joel was suicidal. He was admitted into a psychiatric facility and treated for depression.

Joel describes this period as “a massive rollercoaster ride”, which included many suicide attempts – “more than I can remember”.

He also started to cover parts of his face with those Joker-inspired tattoos, a defence mechanism aimed at creating a barrier between himself and others.

“The Joker is kind of insane, and at the time, because I was so low, that’s exactly how I felt … I just felt like I was insane,” he says.

“It was also this cumulative thing, this feeling that people seemed to want to hurt me – my parents, my army friends and then other people, too – so it was kind of like, well, if I can tattoo my face and deter people from engaging with me, maybe it’s just easier.”

Fast-forward to late 2021. Joel Hartgrove, ACU paramedicine undergraduate, has just completed his first student placement at the Ipswich ambulance station in south-east Queensland.

As he starts to describe his experiences there, Joel’s eyes light up and that warm smile returns to his face.

“It was awesome, like, unreal,” he says. “I had a really good mentor … he was really amazing and it was good to put the skills that I’d learnt at uni into practice.”

Through paramedicine, Joel has rediscovered his sense of purpose. He loves the team-based ethos of the ambulance service, and the high-pressure environment of the job, and he’s learning new skills every day.

“There’s also a sense of pride in doing something to help people. I had a lot of pride every day when I would put on the Australian Army uniform, and for me, it would be the same feeling, putting on the paramedic uniform and doing something useful and important.”

At university, Joel has also found the community he’s always craved. He’s been thankful to meet many other student veterans in his travels.

He still has his occasional dips into depression, but its hold on him is slowly fading, thanks to two things: regular exercise, and a new career focus.

“When I was right at the bottom of that pit, it was pretty horrendous, but once I got back home and doing gym exercise and bodybuilding, it cleared my head so much,” he says.

“Before I knew it, I was starting to think about my next step in life. Paramedicine was the one thing that really stuck out for me. I found a new direction and I found a love for something again, and I’ve never looked back.”

And the tattoos on his face? Well, they’re slowly fading, too, thanks to laser removal therapy.

One day, a few years from now, Joel hopes that strangers will no longer stop and stare. He hopes he won’t be seen as the guy with the tattoos.

“Honestly, I’m really looking forward to the day I longer have them there,” he says.

“I got them for the wrong reasons, and they affect my life greatly, and now that I’m out the other side, I’m so much happier. I feel like a different person. I feel like I’m me again, if that makes sense.”

Are you a current or former member of the Australian Defence Force who is keen to pursue university study? Explore your options at ACU.

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008