Community

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

For as long as he can remember, Adrien McCrory has been fascinated with history. In high school, he would regularly have his nose in a historical novel, or a textbook on medieval Europe or the Russian revolution. He carried this passion into university, discovering his niche in contemporary Australian crime history, and soon found himself reading old court transcripts, “just for fun”.

After completing his degree, however, Adrien took an indefinite hiatus from academic study.

“I wrote my honours thesis on female criminals in twentieth-century Victoria, and then eventually I decided to take a break from academia,” he says.

It was during this period that Adrien came to terms with the fact that he was transgender.

“I had spent a lot of time not being very conscious of my own feelings about my gender, and it was a very slow process, but then I came out and I started to transition and all that sort of stuff.”

Years into this journey, Adrien began to contemplate a return to academia, with a plan to focus on trans histories. He became aware of a PhD opportunity with Professor Noah Riseman, one of his former lecturers at Australian Catholic University (ACU) whose research focuses on histories of gender and sexuality.

“As soon as I saw it, I thought, ‘Oh, I have to go back and do that’,” says Adrien, who is currently completing his thesis on trans and gender-diverse Australians in the criminal justice system across the twentieth century.

“I guess that in some way, it was quite a personal decision to do something that I felt was really important socially, but also on a topic that was very close to me.”

Being a transgender man gives Adrien a unique window into the experiences of the people he comes across in archival sources – whether they are in historical court documents, old newspaper clippings, or oral history interviews.

“As a researcher, I think there’s something very useful in seeing your own experiences, particularly when they’re marginal experiences like trans histories or queer histories, which have often been silenced in the historical record,” he says.

“Doing the work of discovering them and analysing them has an important role to play in showing people that we’ve always been here, and we’ve always faced challenges.”

The process of conducting research into a topic that has for years been suppressed also presents many challenges.

One of the key hurdles is the lack of consistent terminology in historical sources.

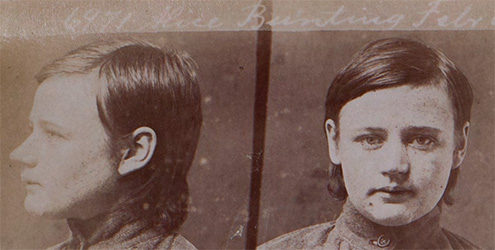

Alice May Bunting: PROV, VA 1464 Penal and Gaols Branch, Chief Secretary's Department, VPRS 516/P2 Central Register of Female Prisoners item volume 13, record page 58

Adrien McCrory’s thesis covers transgender criminal history across the twentieth century, but it wasn’t until partway through the 1900s that language began to emerge in Australia for people who contravene gender norms.

The word “transvestite”, for example, originated from the German sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld, who in 1910 published his book Die Transvestiten.

“Sexologists in Europe were starting to come up with these terms and trying to define them from the late 1800s, but here in Australia, ‘transvestite’ doesn’t really appear until the 1930s and ‘40s,” Adrien says. “Then slowly over time, words like ‘transsexual’ pop up, and it’s not until the 1990s that ‘transgender’ is used consistently to describe trans people.”

In his peer-reviewed article ‘Policing gender nonconformity in Victoria, 1900–1940’, published in Provenance, Adrien contends: “It would be ahistorical to apply the word ‘transgender’ to people in the past who never heard the term and may not have identified with it.”

Rather than avoiding this period altogether, Adrien took the more difficult but ultimately more rewarding course of working through these practical challenges.

“I took a different approach, where I’m finding examples of gender nonconformity, but I’m not looking at the people as though they’re necessarily trans themselves,” he says. “Rather, I’m examining how gender nonconformity was policed at the time – by police officers, courts and prisons – and what that means for the people who were forced to navigate those systems.”

Needless to say, uncovering individual stories in such a fragmented way – through petty sessions, brief newspaper accounts, and prisoner register notes – was a painstaking process.

However, with the use of terms such as “masquerader” – a term used for people who presented as a gender different to the one assigned to them at birth, among other things – Adrien was able to identify several cases that were worthy of close examination.

While Adrien is a self-confessed enthusiast for sifting through old court documents, for his thesis research, it was often the newspapers that provided the colour and detail he was after.

Take the story of Jessie Rogers, a 16-year-old who was arrested for vagrancy in 1901 while dressed in male clothes in Newport, a suburb of Melbourne. While the court records made no mention of Rogers’s clothes or presentation, newspapers ran various headlines including “Masquerading as a man” and “A girl in masquerade”.

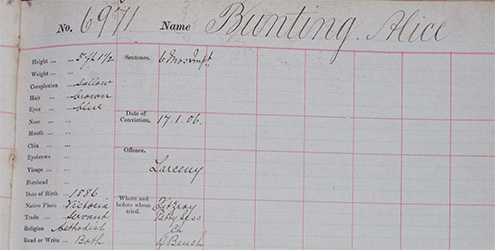

Central register of female prisoners

As Adrien describes in his research, Rogers’s friends and family members noticed a “change in character” in the weeks leading up to the arrest, resulting in a loss of employment. Rogers was termed as “a freak”, “a little bit off her head”, and going through “an erratic turn”, while at the same time being described as a person of “excellent character”.

The case concluded with Rogers’s discharge from court, a positive outcome. However, other defendants received significantly less leeway.

Take Alice May Bunting, who was arrested for vagrancy in 1905 while dressed in male clothes. Bunting was depicted in press reports as poor and disreputable, and described as “covered with dirt”.

“Bunting’s apparent cycle of poverty and crime marked them as a vagrant type and reports did not frame them with the same intrigue or adventurous spirit as they had with Rogers,” Adrien writes in Provenence.

However, he also notes that the police, courts and newspapers generally reserved harsher judgments on male-assumed people who presented as female. These individuals were more likely to be charged with offensive behaviour than vagrancy, and there was a decidedly sexual element to the policing of their cases.

“I think the fact that the people perceived to be male were treated more harshly tells us quite a lot about the ways that gender nonconformity was constructed as being dangerous, or challenging social norms, depending on the gender they assumed the person to be when they came into contact with the criminal justice system,” Adrien says.

Male-assumed defendants were more likely to be associated with homosexuality and sexual deviance, he adds. This was due to the fact that society, the press and the criminal justice system had constructed a “deviant homosexual archetype”, which was framed as “morally and criminally dangerous”.

Overall, Adrien concludes that while a lot has changed for trans and gender-diverse Australia over the last century, the policing of gender nonconformity has a historical legacy that lingers today.

“Though we’ve come a long way, trans people still face alienation and discrimination in many institutions – not only in criminal justice, where they often still have negative contact with police, but also in many other areas.”

The overarching goal of his research is to develop a better understanding of the challenges that trans and gender-diverse people have faced in the past, and continue to face in the present.

“I think we’re currently in a period of heightened scrutiny of trans people, and in many cases, the narratives and discussions have only gotten more intense and more divisive,” Adrien says.

“It feels important for me, both as a historian but also as a trans person, to be diving into these areas that have been so neglected, to challenge the narratives that have been pushed out about trans people, and to lift the silence on the histories that have for so long been suppressed.”

Adrien McCrory is a PhD candidate at ACU. His thesis on the experiences of trans and gender diverse Australians in the criminal justice system across the course of the twentieth century is due to be completed in early 2023. Adrien is a transgender man and is passionate about exploring gender diversity throughout history.

Are you passionate about a career in research and academia? Explore a higher degree by research at ACU.

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008