Community

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

In the late-2000s, when Jason Smeaton was in high school, he developed a keen interest in history. Jason had the fortune of being taught by passionate teachers who helped to fuel his curiosity about the past.

“It was those teachers who gave me that initial drive to learn more about history,” says Jason, who went on to study a Bachelor of Arts with honours in history at the University of Melbourne.

“They encouraged an interest in the past, and they also helped me to see how history can be used to think about current events, how society has changed and how a knowledge of the past helps us to envisage the future.”

As a year 9 student, Jason was a recipient of the Victorian Premier’s Spirit of Anzac Prize, an annual award program that selects students to tour sites where Australians have served in war. On that trip, which included visits to the Burma-Thailand Railway and the Western Front, he met Professor Bruce Scates, a research historian who piqued his interest in a career in academia.

“Being passionate about history and then seeing that it’s actually a path you can take in your life and career, I thought, ‘Ah, this is interesting. This is what I want to do’,” Jason recalls.

He also met Janice McCarthy, a Vietnam veteran who was one of two ex-military representatives on the study tour. Colonel McCarthy was the sole theatre nurse at the 1st Australian Field Hospital at Vung Tau, Vietnam, later serving as Director of the Royal Australian Army Nursing Corps. Her stories of war, and of the service of military nurses who came before her, made a lasting impression on the young Jason Smeaton.

Years later, Jason would investigate the legacy and recognition of Australian army nurses who served in World War One for his honours thesis. His career then took a natural turn into the public service, where he worked as an advisor in a range of government roles.

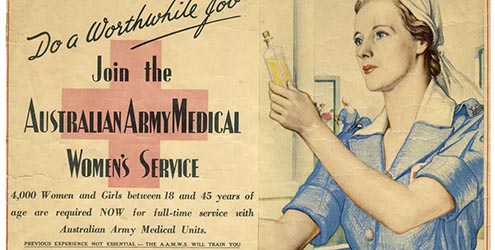

A recruitment poster for the AAMWS, created by artist Napier Waller. Image courtesy of the Australian National Maritime Museum.

“I don’t think I ever stopped being a historian,” says Jason, who still works part-time for a state government agency. “The skills and attributes of historians are really well-suited to the public service – thinking, researching, knowing when something should be questioned and asking the right questions – these are all fundamental to the public service, and it’s a job that I’ve really enjoyed.”

That said, Jason soon felt a pull back to the archives. He left his full-time public service position in 2020 to pursue a PhD under the supervision of one of Australia’s leading humanities academics, ACU’s Professor Joy Damousi.

After almost three years of painstaking research, Jason submitted his PhD thesis. His work explores the experiences of Australian women who served in the army’s nursing auxiliary during World War Two.

“Research is such an exciting challenge. I think that if you’ve got a question that nobody else is looking at and you can see the benefit in it, you really should pursue it,” he says.

“I had questions about the nursing auxiliary and the women who served: Who were they? What work did they do and how did it effect their lives? How did it shape the history of women and the nursing profession more broadly?”

Within the title of Jason Smeaton’s PhD thesis is another key question: “Nurse or not?”

In December 1942, in the middle of the war, the army formally established a women’s auxiliary to provide support to the trained nurses of the Australian Army Nursing Service.

Sergeant J. Baird, AAMWS working at the 115th Australian General Hospital.

Formed out of the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) movement, the auxiliary became known as the Australian Army Medical Women’s Service (AAMWS), referred to colloquially as “am-wahs”.

“So the AAMWS got stuck in the middle of this dispute and the struggles of nurses, who at this point were trying to cement the status of nursing as a profession and a reputable career option for women.”

Alongside this was the public view that women in the nursing auxiliary saw themselves as nurses, even though they hadn’t completed the training required to gain registration. With a strong narrative based on a rich array of archival materials, Jason Smeaton’s thesis shows this perception was based on a myth. Indeed, the women of the nursing auxiliary identified strongly as voluntary aids and AAMWS.

“There were tensions and they did exist, but I’ve been very cautious not to exaggerate the reality of them,” he says. “In the end, these women banded together and realised that within their units they had really strong bonds.”

As Jason writes in an article for Vetaffairs, the official newspaper for Australia’s veteran community, the AAMWS “made a positive contribution to the war effort, and to the nursing profession after the war”.

While Jason’s Smeaton’s PhD has a stated focus of exploring the Australian nursing auxiliary and the effect it had on nursing and women’s work, he says the personal stories of those who served form the most interesting elements of his thesis.

These personal stories – the stories of VADs like Alice Ross King, and AAMWS like Maud Whiting and Janet ‘Jean’ Wallace – bring his research to life.

“There are obviously questions that we can ask as historians, and answers that help to shape what we understand of the past and how we want to design policies for the future, but in my view, it’s the stories that make it important,” he says.

“These are real people whose lives were affected by conflict, and who made massive contributions to the war and to women’s work.”

Until now, the legacy of Australian women who served as auxiliaries has, he says, received very little recognition.

“We know very little about these servicewomen – who they were, the work they did, where they came from before the war and where they went after the war – and that’s one of the reasons why this is a worthwhile examination,” Jason says.

“It can and does change our understanding of that period in Australian history. It raises further questions about how we value people’s contributions, especially women, and as we recognise these contributions, we can think about the effect they had on our society in the past, and also on the society of today.”

Keen to study history at ACU? Explore the options.

Learn more about where higher degree research at ACU could take you.

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008