Community

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

A few years ago, on a routine visit to the State Library of Victoria, cultural historian Mary Tomsic came across a children’s book titled Donkeys Can’t Fly On Planes. Intrigued by the cover image and the mention of refugee children in the tagline, she flicked through to the first story, written by a primary school student named Sunday Garang, who recalled her time in a refugee camp where she was often too starved and sapped of energy to cry.

Sunday was born in the camp in Kakuma, near the Kenya-South Sudan border, and her description of her experiences there, written when she was in the sixth grade, is both poignant and pragmatic.

“I’m not sure I’ve read very many things that describe what people feel like when they’re starving,” says Dr Tomsic, a research fellow with ACU’s Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences. “But this was such a powerful account.”

It is also an account that highlights strength and creativity. Sunday’s mother encouraged her to think about the food they were growing with seeds they had planted. With the help of a donkey named Steven, Sunday collected water for drinking and to help the plants grow.

Interested to find out more, Dr Tomsic approached Kids’ Own Publishing, the Melbourne-based not-for-profit that published the book with 22 child authors and their community in Traralgon, Victoria. She discovered that Donkeys Can’t Fly On Planes was conceived when a teacher was so moved by the stories of her South Sudanese students that she collected them.

The popularity of the book soon prompted the adults in the community to share their own stories of displacement in two subsequent books, In My Kingdom and All the Way Home. Years later, in 2021, a fourth book was published written by younger siblings and community members, titled This is My Home.

As a historian whose research has focused on the impact that stories and images can have on society and people’s lives, Dr Tomsic immediately recognised the books as rich primary source documents that could form the basis of historical learning.

“I think there’s so much richness in culture, in images and in stories, but historians haven’t always directly used these types of sources,” she says.

“They might not provide you with a definitive history of any one issue or group of people, but they do provide the opportunity for conversations to emerge, and I think there are many possibilities that can come from that.”

The sources we use to tell history often determine the types of stories we can tell, and who features in them.

When teaching a history topic such as migration, for example, it is not always easy to find sources that feature children. And yet, as we’ve seen with waves of refugees who have settled in Australia in the post-war period, and in more recent decades, they play a major role in the movement of people to this part of the world.

Dr Tomsic saw the potential for Donkeys and the other two books, written by people whose families had fled conflict in their home nations and migrated to Australia, to provide an insight into how they view their own experiences and journeys.

In collaboration with Kids’ Own Publishing, the History Teachers’ Association of Victoria, and some of the authors of the stories, she led a project to create a set of peer-reviewed resources to be used in history classrooms alongside the three books.

“The purpose was essentially to bring Australian migration and refugee history alive through the voices of children and adults who have lived it first-hand,” says Dr Tomsic, who led the project to completion in late 2019.

“It gives children and teachers the opportunity to use these stories as the basis for learning and thinking about the process of seeking refuge from war and conflict, journeys of migration, and experiences of living in a new country, which are all important parts of Australian history and culture.”

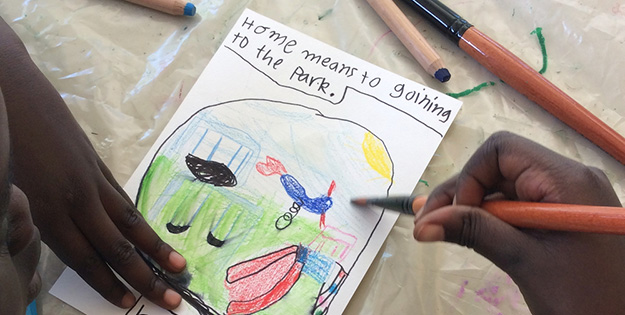

The resources developed through the project include a teacher kit, videos, learning activities and other information to support children’s stories being used as primary sources in the classroom.

In Traralgon, the South Sudanese families whose work features in the books have reported that discussion around them has had an overwhelmingly positive impact.

An author reads his book to storyteller Agum Maluach at a workshop in Gippsland, Victoria

“Some of the community leaders and families say that it’s changed how they’re perceived and understood,” says Dr Tomsic, who believes that similar projects could be rolled out across Australia with different migrant communities.

Donkeys was first published in 2012, and the authors of the stories are no longer children. In 2018, one of them, Angeth Malual, said she hoped the books would open up discussions with different communities in Australia.

“Reading these books and understanding these stories from both parents and children kind of opens people up,” said Angeth, then aged 18.

“If we come to an understanding that we’ve all been through something and we all came from something, at the end of the day we can realise that we’re not that different from each other.”

Over the past decade, Mary Tomsic’s work has focused on the power of images and stories in the context of migration history and Australia’s treatment of refugees.

She has explored the use of childhood refugee images on social media, the artwork of displaced children, the politics of children’s stories, and the way that mainstream picture books can open up spaces for young people to explore the refugee experience.

Dr Tomsic cites popular children’s books like My Two Blankets and Ships in the Field as examples of stories that prompt us to think carefully about critical issues in society. These books contain humanising and thoughtful depictions of displaced children and their families, acting as a counterpoint to the dehumanising and at times misleading pictures seen on the front pages of newspapers.

“These books have a high public profile, and the topics they cover raise some really interesting questions around what adults think children want to know, and also what we think they should know,” she says.

“There are sensitive issues around whether some children should be protected from certain content, and that can be really complex to navigate. But there’s also this idea that these things happen in the world and happen in people’s families, and they are things we should discuss and understand.”

Alongside these popular picture books, the stories in Donkeys Can’t Fly On Planes, In My Kingdom and All the Way Home imbue readers – children and adults alike – with an understanding of the factors that force people to flee their homelands, and how they remake home in new locations.

Moreover, at a time when the world has much more recognition of the rights of children, it is crucial that their voices are heard.

“I’m interested in the idea that we should learn from everyone, and that includes children, and it’s in this interchange of ideas that everyone can learn something and develop more cultural respect,” she says.

“I see some exciting possibilities in that because it raises some very important questions: How do we share stories? How do we build communities? How can we create a more respectful and just society?”

Dr Mary Tomsic is a cultural historian and researcher at ACU’s Centre for Refugees, Migration, and Humanitarian Studies. Her current research project is on visual representations of child refugees, and examines how histories of forced migration are presented through visual records created for, by and about children.

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008