Community

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Nathan Ryan knows what it’s like to visit an inmate behind bars. As a criminologist whose job is to explore the complex issues of crime and criminal justice, he has often had to enter prisons to conduct research interviews with offenders.

But even for someone as practised as him, visiting isn’t easy.

“Through the experience of visiting prisons, it has resonated with me that the process can be quite daunting,” says Dr Ryan, a research fellow and lecturer at ACU’s Thomas More Law School.

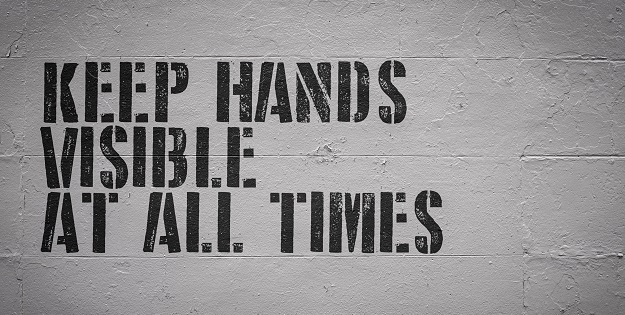

Simply gaining approval to see an offender can be a convoluted exercise: locating the inmate, learning the rules, filling out the forms, making an appointment. Then, once you’ve arrived, which is often after a long journey to a remote location, you’re confronted with high walls, razor wire, stone-faced correctional officers, and other nervous visitors.

“The whole environment is telling you that there’s danger there,” Dr Ryan says. “That can be nerve-wracking and anxiety-inducing – and that’s for someone like me, who isn’t visiting a family member.”

When an offender is sentenced to a prison term, their family members commonly find themselves in a state of uncertainty and – in some cases – shock. Their distress is often compounded when they try to navigate a prison visitation system that is riddled with obstacles.

In an attempt to shed light on their experiences, Dr Ryan and his partner Dr Nicole Ryan, a criminologist at La Trobe University, embarked on ‘The Visitation Project’ – a two-staged study that aims to explore the factors that prevent, delay and increase the likelihood of prison visitation, and how the experience impacts visitors.

The first phase of the research involved a series of confidential in-depth interviews with 21 participants, drawn from a wider sample of 248 respondents to an online survey.

Their responses provide rare insights into the struggles people face when their loved one is incarcerated.

“It was a smack in the face,” said one participant, referred to in the study as ‘Visitor C’. “I was not expecting it at all … I guess I was pretty devastated by what had just transpired, and I felt pretty alone and vulnerable.”

Others likened it to the pain felt if a family member were to suddenly die.

“That’s what’s it like … except worse,” Visitor I told the researchers. “You go home expecting them to be there wanting to talk to them … but it’s worse than a death because they want to be there and you want them there, but they’re not and that’s just the way it is.”

This level of grief can have a profound impact, says Dr Ryan, making the already daunting task of visiting a prisoner seem insurmountable.

“If you look at all the challenges these family members face – the court case, the financial stress, the mental health issues that come from prolonged stress and a sense of loss – you can understand why they feel overwhelmed and inadequately prepared to visit their loved one in prison,” he says.

“Just imagine you had a close family member who was sentenced to murder, and you have 15 years of visits ahead of you and there all sorts of stressful things going on. Add to that a process that can be complicated for most people, where the information is inconsistent and unreliable and difficult to grasp, it’s bound to lead to feelings of frustration and resentment.”

Partly as a result of the barriers faced by family members, most inmates never receive visitors while incarcerated.

That’s unfortunate, says Dr Ryan, because prison visitation has been found to have several benefits, increasing prisoner optimism and lowering the risk of reincarceration.

“Inmates who receive visits tend to be happier and less likely to experience hopelessness, and that has a positive flow-on effect that means they’re better behaved in prison, which reduces the burden on correctional staff who have to deal with unruly prisoners,” says Dr Ryan, who notes that almost half of all prisoners in Australia – some 42 per cent – are reincarcerated within two years of their release.

“On the outside, the literature clearly links visitation with a reduction in recidivism – so offenders are less likely to fall foul of the justice system again, and that’s not only beneficial to these individuals and their families; it’s beneficial to society more broadly.”

For some study participants, the lack of clear information on rules and processes caused problems during prison visits, making it a stressful experience rather than a meaningful one.

“I looked online but I still got in trouble for dress code once,” Visitor L told the researchers. “Lace on the back of my shirt. Not cleavage or it being skin-tight . . . lace … I wouldn’t have worn it if I knew [but] there was no information about that.”

Others eventually gave up seeking information from official sources, instead turning to Facebook groups that support family members of incarcerated people.

“I quickly learned not to bother with the phoneline to the prison to get information,” said Visitor L. “You get in trouble when you go visit because you don’t have something you need, or you have brought something you shouldn’t have, or worn inappropriate clothing, all because you got the wrong information from them… You try to tell the officer this when visiting but they don’t care, they just cancel your visit.”

Dr Ryan adds that despite the proven benefits, prisoner visits have been treated as “a bit of an afterthought”.

In some countries, correctional facilities have moved to severely restrict or eliminate in-person visits. While he has never come across such practices in Australia, Dr Ryan says it is a concern.

“Prisons have historically viewed themselves in their security role – they keep the ‘bad people’ in and stop anything coming into the prison that shouldn’t be there,” he says. “I have this fear that the logical next step is to completely eliminate the security risk of in-person visits, and instead rely on other forms of visitation.”

While the door is currently still open to in-person visits, the study findings show that more needs to be done to make visitation a smoother process.

The researchers argue that simple changes could allow people to better navigate the visitation system – from sentencing, all the way to the visit itself.

“Some people turn up to court expecting their family member to get a suspended sentence, and it can be quite a shock when they see them dragged off in handcuffs and taken to prison – and yet, in many cases, it’s days or weeks before they find out which prison their family members been taken to,” says Dr Ryan, noting that this could be avoided if court-appointed visitation liaison officers were engaged to support friends and family members.

“A person whose sole job is to provide visitation support and point people in the right direction would be a simple way of bridging the gap between the court case and the correctional system, filling in the lack of information that is currently common in the system.”

Prisons could facilitate the visitation process by sharing information with online support groups, he adds, enabling them to swiftly communicate changes to rules and procedures.

“Many of the people we spoke with expressed feeling lost, overwhelmed, fatigued, helpless and desperate for help to allow them to keep contact with their loved ones in prison,” Dr Ryan says.

“We need to fill the information gap that is currently there, and build trust in the criminal justice system among these people who are essentially unintended victims of it.”

Dr Nathan Ryan is a research fellow at ACU’s Thomas More Law School. As well as his work exploring prison visitation, his research has revolved around enhancing the investigation process in homicide cases, and perceptions of rape trial testimony. You can find him on Twitter/X at @Drnathanryan.

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008